Afrolatinidad: Art & Identity in D.C. is an interview series highlighting the vitality of the local Afro-Latinx community. Before the term Afro-Latinx entered popular discourse, Latin Americans of the Diaspora have been sharing their stories through artistic manifestations online and in community spaces throughout the district. Their perspectives are intersectional in nature of existing in between spaces of Blackness and Latinidad. Explore the series on Folklife Magazine .

Elexia Alleyne and her family have lived in what they call “the barrio of Washington, D.C.” for three generations. Last fall, I met with her at her grandmother’s apartment, where the neighborhoods of Columbia Heights and Adams Morgan meet.

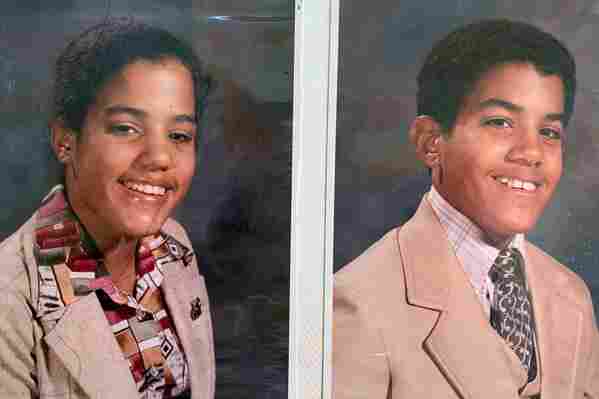

Her grandmother, Andrea Balbuena, is the family matriarch and a proud “old-school Dominican” immigrant. Andrea arrived in D.C. from the Dominican Republic in 1963. When Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated on April 4, 1968, Andrea had just given birth to Elexia’s mother and uncle at three months premature and was caught among the outrage of the district’s grieving residents.

“My grandma lived closer to Fourteenth Street at that time, and she was scared that the rioting would spill into the neighborhoods, not just the commercial areas,” Elexia recounts. “My mom and uncle were still under observation at GWU Hospital. She didn’t have a license. She didn’t own a car. Her only mode of transportation was the bus. Being a single mother with all of that going on, she was under so much personal stress. I’m sure she felt very afraid and isolated. The Hispanic community was very small back then, and she didn’t know any English. She understood discrimination and the significance of Dr. King’s death, but she didn’t grasp the concept of why people were rioting.”

Generationally, Elexia and Andrea have contrasting experiences on racial heritage. Although they’re extremely close, her grandmother’s perception of desirable beauty standards does not run parallel to Elexia’s rejection of what pretty “should” look like, fueled by an eagerness to embrace her African heritage. Elexia attributes that to being born in the United States and her generation’s attitude toward critiquing racial bias in their families and in themselves.

“There’s colorism and racial discrimination in America, as there is in the Dominican Republic,” Elexia says. “The DR is stuck in the last century in terms of not embracing Blackness. The only ‘woke’ Dominicans I’ve seen who embrace all that they are, are the people who come here. With Abuela, it’s always a thing about features and what’s more desirable. She always makes fun of my nose. It’s a big joke between us. I take it all with a grain of salt. She was raised in the ’40s. there was a lack of representation of authentic Black women being regarded as beautiful in media.”

Growing up in D.C.’s barrio , Elexia remembers a vibrant, tight-knit Dominican community embedded within the larger neighborhood. She attended the Spanish bilingual public school Oyster-Adams, where she first became acquainted with her identity as an Afro-Latina. She remembers feeling othered at lunch time, comparing her plate of mangú y salchichón to her peers’ peanut butter and jelly sandwiches.

“Oyster was a predominately white school with a few Latinos sprinkled around. When I tried to connect with other Latinos, even though we had the same native tongue, there was always a disconnect with my experience and what I could relate to. That’s how I started realizing that with my Black American friends, I was able to relate to their experience more. I knew I was Black, I knew I was Latina, but I never wanted to hijack my friends’ Black American experience because I knew that was not my own. But I also knew that I didn’t fit into the Central American Latino experience. I’ve always felt like a Venn diagram, pulling from everywhere.”

In her experience, the Latino community in D.C. is siloed by nationality group, which Elexia attributes to the presence of Blackness, on how it both unites and separates her community . When she was growing up, organizations like the Latin American Youth Center , CentroNía , and La Union DC played a pivotal role in opening doors for Elexia to connect with other Latin American youth and develop her love for poetry.

“The first poem I put on paper was in the sixth grade, for a poetry competition around Valentine’s Day, and I won. The next year I entered again. I was in my grandma’s mirror freestyling a poem in the mirror, with my mom writing it down. It makes me feel good that I have a piece that resonates with people today and that little seventh-grade me was onto something. Poetry is an outward proclamation of who I am . I’m speaking out on what is our truth versus how it’s interpreted. In many ways, I wrote myself out of darkness.”

By Elexia Alleyne

Maybe it’s the Spanish running through my veins That’s the only way I know how to explain it Maybe it’s the r’s rrrolling off my tongue See, When I speak in Spanish It takes the air from my lungs The love for my culture reaches the sky The love for my culture will never die And while you get up and have your milk and cereal Siempre desayuno con platano de mangu Not no cheerios I always mix it up Con salsa y merengue Constantly side ways glanced at Like, she speak no ingles Yo si puedo hablar, ingles y espanol Hasta puedo entender dos y tres Languages! Confronted with problems like immigration Forced to have my parties down in the basement Confined to the more popular story that my family Criss, crossed, and slid past borders Trying to find a new place to live Guilty of chasing paper without papers but when that visa is blinking green It’s saying “Go, go m’jita! Fight for your dreams!” See, My mother came here with a belly full of liberty and hope She bore them both Naturalization the wiping out of my roots made legal under oath invisible legally but constantly contributing economically Corporate America doesn’t want to see me The fields y los barrios embrace queen My culture has this game on choke hold Americana y Dominicana means I’m worth gold With traditions so deep And a passion this strong The love for my culture Will forever live on

At fifteen, Elexia joined the D.C. Youth Slam Team at Split This Rock , followed by the Words Beats & Life slam team. Toward the end of high school, she wrote and performed with F.R.E.S.H.H. (Females Representing Every Side of Hip-Hop). Many of her poems draw inspiration from the love of her culture. Writing poetry was Elexia’s way of reclaiming her identity, paying homage to her family’s struggle—a love letter to her ancestors.

“The spoken word component of poetry was my avenue to not only experiment with wordplay but to test how far I could manipulate literal and figurative meaning at the same time,” she explains. “In short, I lived for metaphors that could be taken at face value and then unpacked for a deeper message. I intentionally wrote to touch and elevate folks intellectually.”

“‘Mamacita’ plays on two very familiar stereotypes associated with Latinx and Black heritage. The poem tells the story of using prevalent adversities to strengthen an inner sense of perseverance and ambition all while being the truthsayer of a generation. I truly believe that the poem itself is a self-fulfilling prophecy that I wrote myself into. I am quite literally using my truth and creative sense of expression to reach and educate the youth.”

After high school, Elexia majored in speech pathology at Old Dominion University, but it was her special education classes that sparked a desire to pursue a career in education. She is currently pursuing her master’s degrees in special education at American University. Poetry has become the motivating factor behind her process as a teacher. She uses poetry as an educational tool to free her students from mental constraints, shedding the conventions of writing that halt students in their quest for self-expression. By exposing them to the world of poetry, Elexia opens the door to new ways of thinking and conceptualizing the world.

“Being a special education teacher gives you so much insight into how the minds of students with different abilities work. The beauty of poetry is that this art is freeing of those restraints that can be difficult for my students. Poetry is the fun part of teaching. It’s the flexible part. It’s what makes me relatable to my kids.”

As an art educator myself, I have experienced firsthand the power that storytelling has to reveal truths that may have otherwise stayed locked inside. Storytelling is emblematic to the Afro-Latinx experience. Be it through music, visual arts, or poetry, telling the stories of ourfamilies and our communities is how many first-generation Americans come of age in the exploration of race and identity.

“There is no right way to poetry, and that’s what makes it so accessible,” Elexia says. “I like to think that poetry is the skill, and what you do with it is the talent. Watching kids create and discover their voice using poetry is a reward within itself. That’s what motivates me.”

For Elexia and myself, art education is not an extension of the artistry but the work itself. It’s about exposing untold stories of the people who make up the fabric of our local communities, to empower the younger generation of artists with the skills and courage to be the next truthsayers and change makers.

Carolina Meurkens is an MFA candidate in creative nonfiction at Goucher College and a fellow in the Smithsonian’s Internship to Fellowship (I2F) program at the Center of Folklife and Cultural Heritage. She is a musician and writer, taking inspiration from the sounds and stories of the African diaspora across the Americas and beyond.