Kidnapped, beaten and left to die, Edmonia Lewis, a talented artist with both African and Native-American ancestry, refused to abandon her dreams. In the winter of 1862, a white mob had attacked her because of reports that she had poisoned two fellow Oberlin College students, drugging their wine with “Spanish Fly.” Battered and struggling to recover from serious injuries, she went to court and won an acquittal.

Though these details are apparently true, after becoming an internationally known sculptor, Lewis used threads of both truth and imagination to embroider her life story, artfully adding to her reputation as a unique person and a sculptor who refused to be limited by the narrow expectations of her contemporaries.

Among the collections of the Smithsonian American Art Museum are several of Lewis’ works, and her most significant work, The Death of Cleopatra , greets visitors who climb to the museum’s third floor in the Luce Foundation Center. Many of Lewis’s works disappeared from the art world, but her image of Cleopatra found its way back from obscurity after a decades-long sojourn that carried its own strange story of fame and lost fortunes.

Lewis shattered expectations about what female and minority artists could accomplish. “It was very much a man’s world,” says the museum’s curator Karen Lemmey . Lewis, she says, “really broke through every obstacle, and there’s still remarkably little known about her. . . . It’s only recently that the place and year of her death have come to light—1907 London.”

The artist proved to be particularly savvy about winning over supporters in the press and in the art world by altering her life story to suit her audience. “Everything that we know about her really must be taken with a grain of salt, a pretty hefty grain of salt, because in her own time, she was a master of her own biography,” says Lemmey. Lewis shifted her autobiographical tale to win support, but she did not welcome reactions of pity or condescension.

“Some praise me because I am a colored girl, and I don’t want that kind of praise,” she said . “I had rather you would point out my defects, for that will teach me something.”

Lewis’s life was profoundly uncommon. Named Wildfire at birth, she apparently had a partially Chippewa mother and a Haitian father. Lewis claimed her mother was full-blooded Chippewa, but there is disagreement on this point. That parentage set her apart and added to her “exotic” image. Her father labored as a gentleman’s servant, while her mother made Native-American souvenirs for sale to tourists.

After both parents died when she was young, Lewis was reared by maternal aunts in upstate New York. She had a half-brother who traveled west during the Gold Rush and earned enough money to finance her education, a rare opportunity for a woman or a minority in the 19th century. She was welcomed at the progressive Oberlin College in 1859, but her time there was not easy. Even after being cleared of poisoning charges, Lewis was unable to finish her last term at Oberlin following allegations that she had stolen paint, brushes and a picture frame. Despite dismissal of the theft charges, the college asked her to leave with no chance to complete her education and receive her degree.

She moved to Boston, again with financial assistance from her half-brother. There, she met several abolitionists, such as William Lloyd Garrison , who supported her work.

Unlike white male sculptors, she could not ground her work in the study of anatomy. Such classes traditionally were limited to white men: however, a few white women paid to get a background in the subject. Lewis could not afford classes, so she engaged her craft without the training her peers possessed. Sculptor Edward Brackett acted as her mentor and helped her to set up her own studio.

Her first success as an artist came from sale of medallions she made of clay and plaster. These sculpted portraits featured images of renowned abolitionists, including Garrison, John Brown and Wendell Phillips, an advocate for Native-Americans. But her first real financial success came in 1864, when she created a bust of Civil War Colonel Robert Shaw , a white officer who had commanded the 54th Massachusetts infantry composed of African-American soldiers. Shaw had been killed at the second battle of Fort Wagner, and contemptuous Confederate troops dumped the bodies of Shaw and his troops into a mass grave. Copies of the bust sold well enough to finance Lewis’s move to Europe.

From Boston, she traveled to London, Paris and Florence before deciding to live and work in Rome in 1866. Fellow American sculptor Harriet Hosmer took Lewis under her wing and tried to help her succeed. Sculptors of that time traditionally paid Roman stone crafters to produce their works in marble, and this led to some questions about whether the true artists were the original sculptors or the stone crafters. Lewis, who often lacked the money to hire help, chiseled most of her own figures.

While she was in Rome, she created The Death of Cleopatra , her largest and most powerful work. She poured more than four years of her life into this sculpture. At times, she ran low on money to complete the monolithic work, so she returned to the United States, where she sold smaller pieces to earn the necessary cash. In 1876, she shipped the almost 3,000-pound sculpture to Philadelphia so that the piece could be considered by the committee selecting works for the Centennial Exhibition, and she went there, too. She feared that the judges would reject her work, but to her great relief, the panel ordered its placement in Gallery K of Memorial Hall, apparently set aside for American artists. Guidebook citations of the work noted that it was for sale.

“Some people were blown away by it. They thought it was a masterful marble sculpture,” says Lemmey. Others disagreed, criticizing its graphic and disturbing image of the moment when Cleopatra killed herself. One artist, William J. Clark Jr. wrote in 1878 that “the effects of death are represented with such skill as to be absolutely repellent—and it is a question whether a statue of the ghastly characteristics of this one does not overstep the bounds of legitimate art.” The moment when the asp’s poison did its job was too graphic for some to see.

Lewis showed the legendary queen of ancient Egypt on her throne. The lifeless body with head tilting back and arms splaying open portrays a vivid realism uncharacteristic of the late 19th century. Lewis showed the empowered Cleopatra “claiming her biography by committing suicide on her throne,” says Lemmey. She believes Lewis portrayed Cleopatra “sealing her fate and having the last word on how she’ll be recorded in history,” an idea that may have appealed to Lewis.

After the Philadelphia exhibition ended, this Cleopatra began a life of her own and an odyssey that removed the sculpture from the art world for more than a century. She appeared in the Chicago Interstate Industrial Expo, and with no buyer in sight within the art world, she journeyed into the realm of the mundane. Like legendary wanderers before her, she faced many trials and an extended episode of mistaken identity as she was cast in multiple roles. Her first mission was to serve as the centerpiece of a Chicago saloon. Then, a racehorse owner and gambler named “Blind John” Condon bought her to place on the racetrack grave of a well-loved horse named after the ancient leader. Like a notorious prisoner held up to ridicule, the sculpture sat right in front of the crowd at the Harlem Race Track in Forest Park, a Chicago suburb. There, Cleopatra held court while the work’s surroundings morphed.

Over the years, the racetrack became a golf course, a Navy munitions site, and finally a bulk mail center. In all kinds of weather, the regal Egyptian decayed as she served as little more than an obstacle to whatever activity was occurring around it. Well-meaning amateurs tried to improve her appearance. Boy Scouts applied a fresh coat of paint to cover graffiti that marred its marble form. In the 1980s, she was handed over to the Forest Park Historical Society, and art historian Marilyn Richardson played a leading role in the effort to rescue her.

In the early 1990s, the historical society donated the sculpture to the Smithsonian, and a Chicago conservator was hired to return it to its original form based on a single surviving photograph. Although the museum has no plans for further restoration, Lemmey hopes that digital photo projects at institutions around the world someday may unearth more images of the sculpture’s original state.

Just as the sculpture’s history is complicated and somewhat unclear, the artist herself remains a bit of a mystery. Known as one of the first black professional sculptors, Lewis left behind some works, but many of her sculptures have disappeared. She had produced a variety of portrait busts that honored famous Americans, such as Abraham Lincoln, Ulysses S. Grant, and Henry Wordsworth Longfellow .

During her first year in Rome, she produced Old Arrow Maker , which represents a portion of the story of Longfellow’s "The Song of Hiawatha" —a poem that inspired several of her works. White artists typically characterized Native Americans as violent and uncivilized, but Lewis showed more respect for their civilization. This sculpture also resides at the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Her first major work, Forever Free (Morning of Liberty) , was completed a year after her arrival in Rome. It shows a black man standing and a black woman kneeling at the moment of emancipation. Another work, Hagar, embodies the Old Testament Egyptian slave Hagar after being ejected from Abraham and Sarah’s home. Because Sarah had been unable to have children, she had insisted that Abraham impregnate her slave, so that Hagar’s child could become Sarah’s. However, after Hagar gave birth to Ishmael, Sarah delivered her own son Isaac, and she cast out Hagar and Ishmael. This portrayal of Hagar draws parallels to Africans held as slaves for centuries in the United States. Hagar is a part of the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s collection.

While many of her works did not survive, some of Lewis’s pieces now can be found at the Howard University Gallery of Art , Detroit Institute of Arts , the Metropolitan Museum of Art , and the Baltimore Museum of Art . Lewis recently became the subject of a Google Doodle that pictures her working on The Death of Cleopatra . Also, the New York Times featured her on July 25, 2018 in its "Overlooked No More" series of obituaries written about women and minorities whose lives had been ignored by newspapers because of the cultural prejudice that revered white men.

San Antonio Displays More Than 100 Sculptures by Artist Sebastian

Towering above the intersection of Alamo and Commerce streets near the banks of San Antonio’s famous River Walk sits a monument that has become an important emblem of the Texas city’s art scene. Known as The Torch of Friendship , the 65-foot, reddish-orange steel sculpture is the work of Sebastian , a sculptor hailing from Mexico who created the 45-ton abstract installation on behalf of the local Mexican business community, which gifted the piece to the city of San Antonio in 2002. In the years since, it has become a recognizable part of the city’s landscape.

Now, 17 years later, the City of San Antonio Department of Arts and Culture welcomes back the 71-year-old sculptor for a massive retrospective of his extensive career. Called "Sebastian in San Antonio: 50+ Years | 20+ Locations | 100+ Works," the citywide exhibition , which kicks off today and runs through May 2020, features dozens of works from Sebastian’s personal collection and spans the artist’s 50-plus year career. Pieces will be on display at a number of the city’s most important cultural institutions, including the McNay Art Museum, Texas A&M University-San Antonio, the Mexican Cultural Institute, the Spanish Governor’s Palace and numerous libraries and outdoor plazas.

"This exhibit reflects the eternal bond between San Antonio and Mexico, which dates before 1836 when San Antonio and Texas were part of Mexico," says Debbie Racca-Sittre, director of the City of San Antonio's Department of Arts and Culture. "Every aspect of the exhibition reflects on the connection San Antonio and Mexico have with one another, from the artist, who splits his time between Mexico City and San Antonio, to the opening venue of the Instituto Cultural de México, which was established as a permanent cultural representation of the Mexican government in San Antonio after the 1968 World’s Fair on the site of the Mexican Pavilion."

Born Enrique Carbajal González, Sebastian adopted his pseudonym after seeing a painting called St. Sebastián by Italian Renaissance painter Sandro Botticelli. Over the years, he’s received numerous awards for his work and has been featured in nearly 200 solo exhibitions at museums throughout the United States, Germany, Spain, Japan, France and more. He has created permanent installations around the world out of his preferred mediums of steel and concrete, and was inducted into the Royal Academy of Art at The Hague, a fine arts academy in the Netherlands.

Not only does the artist's work transcend borders, but it also gives strength to a community whose roots run deep and play an important role in the cultural fabric of San Antonio.

"With 63 percent of San Antonio’s residents identifying as Hispanic, and a majority of this population having Mexican roots, San Antonio’s culture is deeply influenced by the traditions, heritage and history of Mexico," Racca-Sitte says. "[This exhibition] signifies much more than the mathematical equations Sebastian’s art visually represents. It symbolizes the compassion, kindness, understanding and connection that art can build between seemingly different places and people."

Smithsonian magazine caught up with Sebastian before the debut of the exhibition to discuss what inspires him, the importance of marrying science and technology with art, and the challenges he faces creating such enormous installations.

Why was San Antonio chosen as the city to host this major retrospective of your work?

About 20 years ago, I designed The Torch of Friendship . Growing up in Santa Rosalía de Camargo in Chihuahau, a state in Mexico that borders the United States, I would often travel north. Since my adolescence, I’ve always loved San Antonio, and it plays an extremely important role in the historical and economical relationships between the United States and Mexico.

Much of the retrospective will include pieces from your private collection. What was the selection process like when it came to deciding which works would make the cut?

The selection of the pieces are from both sides, from the city and from my own personal collection. I chose pieces that teach a little bit about what my work signifies, which is the creation of the language of a concept, and is a vision of nature—my vision of the contemplation of the macrocosms and microcosms in which I exist.

Did you create any new works for this exhibition?

Yes, there’s a new piece that is really beautiful and that I personally like a lot. It’s called Texas Star , and it signifies the strength of Texas. Like the majority of my work, it’s a metal sculpture.

Were you inspired by the city of San Antonio while making this new work?

I wanted to show how similar San Antonio is to my native land of Chihuahua and the strength of the people who live there. I also wanted to tell the story of the beginning of humanity, and about dolmens and menhirs, two of the first structures constructed by man. [Dolmens are megalithic structures typically formed from a large horizontal stone slab resting on two or more upright slabs, while menhirs are large, man-made upright stones usually dating to the Bronze Age of Europe.] This piece evokes those elements as a big star that glows with the light of the sun.

You’ve said in the past that the future of art is science and technology. Can you expand on this idea and give some examples of pieces that integrate science and technology?

A great majority of my pieces that will be exhibited are spheres and are from the series Quantum Spheres , which is inspired by quantum physics. I was inspired by mathematics and geometry when I created these pieces. Technology is always taken into account whenever I make a piece. I use a computer when making all of my works to ensure that they’re built correctly and are structurally sound.

What are some of the challenges you face creating such enormous sculptures?

When creating monumental sculptures, you need to think like an engineer, an architect and an urbanist all in one in order to design these kinds of structures. The difficulty is the calculations and implementing the correct structural strategies so that the designs are stable and don’t provoke a catastrophe.

How Artist Teresita Fernández Turns Graphite, the Stuff of Stardust, Into Memories

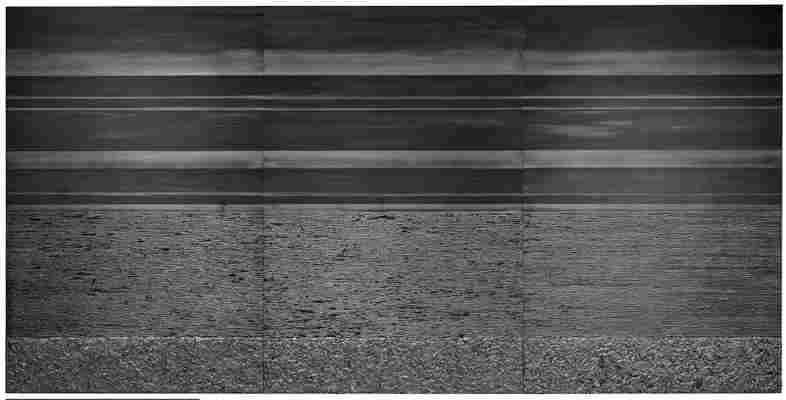

From a distance, contemporary artist Teresita Fernández’s sculpture Nocturnal (Horizon Line) appears to be a simple, modern rectangle of silvery gray. In the artist’s words , “when approached directly, you see nothing, just a simple dark gray rectangle. But when you start moving, the pieces become animated. . . . It’s almost as if the image develops before your eyes.”

Gradations of color and texture emerge, forming three distinct horizontal bands. The first, smooth and flat, evokes the sky. The second, shiny and polished, nods to water. The third, chunky and organic, represents the Earth.

The differences in consistency are made possible by Fernández’s use of graphite, a mineral formed over thousands of years under the Earth’s surface. A new episode of “Re:Frame,” a video web series produced by the Smithsonian American Art Museum, investigates the compelling role graphite has played in the history of art—and in Fernández’s work.

“Teresita Fernández is a researcher in many ways and she's also a conceptual artist,” says E. Carmen Ramos , curator of Latino art and the museum’s deputy chief curator.

Born in Miami in 1968, Fernández received her BA from Florida International University and an MFA from Virginia Commonwealth University. In 2005, she was awarded a MacArthur “Genius” grant and, in 2012, President Obama appointed her to the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts. Her sculptures and installations can be found in museums throughout the world, including the Smithsonian American Art Museum .

Fernández’s work focuses on the natural world, which she explores using unconventional methods and materials. “She's created images of cloud formations, volcanic eruptions and bodies of water,” says Ramos. “In many cases, she uses a wide variety of materials to create these illusions that become experiences for the viewer.” To create Nocturnal (Horizon Line), the artist investigated the material properties of an unexpected substance: graphite.

“Graphite is a naturally-occurring mineral. It occurs all over planet Earth, and in space, and it's formed just of the element carbon,” says Liz Cottrell , curator-in-charge of rocks and ores at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C.

“Humans, animals and plants are composed of carbon. We, humans, are carbon-dominated lifeforms, and when we die, our bodies and tissues decompose, and under heat and pressure in the Earth, organic carbon turns into graphite,” says Cottrell.

Though often mistaken for lead, the workhorse material at the end of our pencils is actually graphite. According to Cottrell, “graphite is super soft, and that's because the carbon atoms are arranged in plains, in sheets, and those sheets simply sluff off when you rub it.”

Graphite has been a popular art-making material since the 16th century. It was a favorite of Renaissance master Leonard da Vinci, who used graphite to create some of the earliest “landscapes” in Western art history.

Prior to da Vinci’s time, artists considered nature a backdrop—not a subject—for artwork. Da Vinci was among the first to create drawings that foregrounded nature, celebrating the landscape rather than human civilization. “There is this deep connection with graphite, which is related to pencils and the depiction of landscapes,” says Ramos.

“One of the most popular graphite localities historically is in England. . . where pencils were first developed,” says Cottrell. Borrowdale, in the Cumbria region, became particularly famous among Renaissance artists for its high-quality deposits. Even before da Vinci began drawing with Cumbrian graphite, English shepherds used it to identify their flocks by marking the wool of their sheep.

The development of landscape as an artistic focus, and its connection to the material graphite, served as the inspiration for Nocturnal (Horizon Line) . As an artist whose work centers on the natural world, Fernandez was drawn to the physical location—and material—that inspired the genre she continues to explore.

While da Vinci sketched with a graphite pencil, Fernández sculpts with graphite itself. “She was really intrigued with this idea of creating a picture whose material is intimately and completely integrated with the image that she's creating,” says Ramos.

But Fernández is not depicting Borrowdale in Nocturnal (Horizon Line) —or any specific landscape.

“When you think about historic landscapes from the 19th century by Thomas Moran and Frederic Church, they represent very specific places, right? Whether it's the Chasm of Colorado or the Aurora Borealis ,” says Ramos. “When you look at this work, it has a kind of generic feel.”

“Teresita Fernández is not interested in depicting a specific place, but is really interested in triggering our personal associations, a visitor’s personal association, with a place of their own choosing,” Ramos says.

Grounded in centuries of art history and millennia of geological processes, Teresita Fernández’s sculpture Nocturnal (Horizon Line) is ultimately about personal experience—it’s the stuff of stardust evoking memories. Her use of graphite connects the sculpture to the land, but its lack of specificity allows viewers to project their own setting, either imagined or remembered, onto its shimmery surface.

“Whenever I look at it, I think of when I lived in Chicago and all of my walks looking at Lake Michigan. It has that experience for me. While it's not depicting Lake Michigan, it triggers that memory in my personal history,” says Ramos.

Teresita Fernández' 2010 Nocturnal (Horizon Line) is on view on the third floor, east wing of the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C.