Last September, the Smithsonian’s Hirshhorn Museum underwent a makeover of epic proportions when Korean artist Lee Ufan installed ten site-specific sculptures around the cylindrical building's exterior. On display through September 13, 2020, “ Lee Ufan: Open Dimensions ” gives visitors the opportunity to experience sleek steel and stone artworks that blend seamlessly into the museum’s 4.3-acre site beside the National Mall.

That’s not the only outdoor art gracing the Smithsonian campus. Since May, bright, storybook-like houses and giant dragonflies, grasshoppers and nests have spread among the museum properties. All 14 installations are part of an exhibition organized by the Smithsonian Gardens that explores a central theme: “protecting habitats protects life.”

And there’s more to come. Starting this May, two public artworks— Monument by New York City-based artist Maren Hassinger and Marker by Washington, D.C.-based artist Rania Hassan —will be installed along D.C.’s Connecticut Avenue. Both pieces explore the history of women in public and private life, and are part of an effort by the Smithsonian Institution and the Golden Triangle Business Improvement District to extend the Smithsonian’s American Women’s History Initiative into the city’s streets.

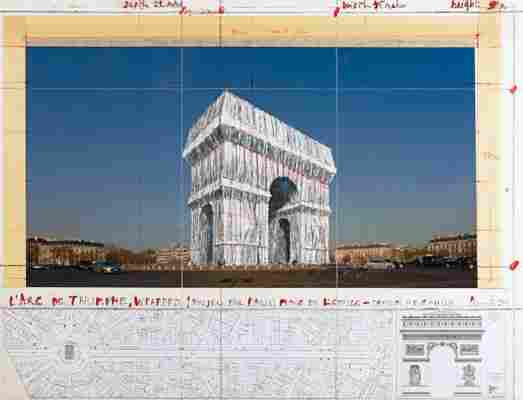

All of this excitement on our home turf has us anticipating a number of big, bold art installations beyond the Smithsonian. From Janet Echelman’s massive web-like weavings, which are large enough to cover entire buildings and city blocks, to the 60-year-in-the-making idea by the artist Christo and his now deceased collaborator Jeanne-Claude to shroud the Paris' iconic Arc de Triomphe in cloth, the outdoor sculpture scene for the year ahead proves that the sky is truly the limit.

Growing up, Yayoi Kusama lived on her family’s nursery and seed farm in Japan, where she roamed the open fields bursting with flowers and explored the property’s greenhouses. Over the years the natural world would become a reoccurring theme in the now 90-year-old contemporary artist’s sculptures and paintings. So it should come as no surprise that the venue for her latest solo exhibition would be the New York Botanical Garden in New York City. Opening May 9, “Kusama: Cosmic Nature” is a “multisensory presentation” that will include the debut of two new sculptures, Dancing Pumpkin (2020), a 16-foot-tall sculpture, and I Want to Fly the Universe (2020), a 13-foot-tall "biomorphic form with a yellow face and polka dots," as well as Flower Obsession (2020), an interactive piece where museumgoers can stick flowers on walls to create a collaborative masterpiece. Also on display: her popular Infinity Mirror Room . The show comes on the heels of her "One with the Eternity: Yayoi Kusama in the Hirshhorn Collection" exhibition —a tribute to the artist's seven-decade career—that opens April 4 at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, D.C.

In 1962, design duo Christo and Jeanne-Claude imagined a project of epic proportions: wrapping Paris’ famed Arc de Triomphe from top to bottom in fabric. Over the years, the renowned artists revisited the idea again and again, creating dozens of sketches of their larger-than-life project. Unfortunately, in 2009, Jeanne-Claude died and the project was scrapped—that is until now. This September, nearly 60 years later, Christo will finally bring their design to life by wrapping the 162-foot-tall, 150-foot wide structure in 269,000 square feet of silvery-blue recyclable polypropylene fabric and tying it up with 22,965 feet of red rope.

Journalist Nellie Bly made a name for herself when she went undercover posing as a patient at the women's asylum on Blackwell’s Island (now Roosevelt Island) in New York City. Her reporting for the New York World pulled back the curtain on the atrocities and abuse that patients endured there, and by 1887 her reportage became a book called Ten Days in a Mad-House . Now, 130 years later, Bly’s work is being commemorated with the unveiling of The Girl Puzzle , a sculptural installation by artist Amanda Matthews of Prometheus Art . Appropriately situated on Roosevelt Island, the series will debut this summer and will feature five seven-foot tall female faces, including one representative of Bly. According to the artist’s statement, each bronze-cast piece “shows the depth of emotion and complexity of being broken and repaired,” a challenge that Bly overcame at the asylum.

With each passing second, artist Janet Echelman ’s massive installations transform based on a site’s wind speed and direction and the natural light. Using engineered fibers, which she weaves together masterfully to make colorful netting, Echelman , who was awarded a Smithsonian American Ingenuity Award in 2014, marries the ancient craft of weaving with modern-day computer design software to create works that are large enough to cover entire buildings and city blocks. For 2020, she has announced a multitude of installations that will be debuting around the world, including Earthtime 1.26 (D.C.) at the By the People Festival, Washington, D.C. (June 12 through 28); Noli Timere at the Palazzo del Senato in Milan, Italy (April 20 through 27) and Los Angeles (October 2020 through March 2021); and 1.78 (Helsinki) at the Helsinki Biennial (August 2020) in Helsinki, Finland. Though indoors, Echelman's 1.8 Renwick will hang in the Smithsonian's Renwick Gallery in Washington, D.C. from April 3 to August 14, 2022.

Dale Chihuly has made a name for himself for his intricately designed tangles of glass, which have been displayed at world-class museums and important cultural sites around the world, from Iceland and Italy to Australia and Brazil. For his latest exhibition, the Seattle-based artist is sticking a little closer to home with " Chihuly at Cheekwood ." Opening April 25, the exhibition celebrates the 60th anniversary of Cheekwood , an estate dating back to the 1930s that’s surrounded by 55 acres of gardens, and will feature a variety of large-scale glass installations, including two new site-specific pieces. The exhibition also looks back on Chihuly’s first show at Cheekwood, which took place a decade ago in 2010.

Since 2014, Winter Stations , an international design competition and exhibition, has become the local art community’s ticket to getting through the winter doldrums. To be held at the city’s Woodbine Beach from February 17 through March 30, the annual exhibition will feature installations created by artists from around the world who have been selected to find innovative ways to alter the beach’s unused lifeguard stations into works of art. Winning entries for 2020 include Noodle Feed by iheartblob , an art collective from Vienna, Austria, that uses recycled sailcloth to create interactive tunnels or “noodles,” and Mirage , a piece by Christina Vega and Pablo Losa Fontangordo of Madrid, Spain, that mimics the sun either rising or setting, depending on viewers’ vantage points.

The work of artist and designer Olalekan Jeyifous , Wrought, Knit, Labors, Legacies is the second installation to be featured as part of Alexandria’s "Site See: New Views in Old Town," an annual public art series. For his site-specific installation, Jeyifous examined Alexandria’s African-American history in relation to its time as an industrial heavyweight, serving as not only a major port city but also home to Franklin and Armfield, the largest domestic slave-trading firm in the nation at the time. Weaving together the city’s storied—and infamous—history, Jeyifous created a series of large-scale faces in profile adorned with symbols nodding to the local industry, such as factories, tobacco warehouses and railways. The piece will run from late March to November.

Denis Augé describes himself as a “stone charmer,” and with one look at his creations, it’s easy to see why. Augé has dedicated his career to the art of masonry, taking stones and assembling them into large-scale structures in which he purposely leaves behind empty spaces in each piece to allow the transference of light, creating a juxtaposition of light and dark that changes depending on the location of the sun. For his latest exhibition, the self-taught French artist has created five pieces that will be unveiled at Château de Belcaste l on April 2 that explore "the relationship between architectural forms and bold contemporary vision.”

It’s been 17 years since the first Swell Sculpture Festival took place. The idea behind it was simple: Create a free art experience that is open to everyone. Now, nearly two decades later, the festival has swelled from being an exhibition featuring 23 sculptures attended by 6,000 people to a massive multi-day event that last year lured a crowd of approximately 265,000 viewers from around the world. Highlights of the 2019 festival included artist Karl Meyer's Hand in the Sand , which resembled a giant's fingertips breaking through the earth, and Jaco Roeloffs' Superegg , a nearly 7-foot tall work that looks like it's covered in gemstones but in reality is bejeweled in 3,000 used coffee pods. While artists' applications are still being accepted for the 2020 event at Currumbin Beach, Gold Coast, Queensland, Australia (September 11 through 20), if the previous festivals are any indication, this one will be larger than life.

Alicja Kwade’s Installation at the Hirshhorn Invites Viewers to Question the World as We Know It

Alicja Kwade’s installation WeltenLinie is full of dualities. It is simultaneously structured and whimsical, sensible and illusory. This is a reflection, she says, of the human need to systematize the unknowable.

“It’s a kind of tragic thing to be a human being because we are trying so hard to understand the world, but actually, there is no chance,” says the Berlin-based artist. “We are building systems, political structures or religions to make this doable and as easy as possible to survive in it. Actually, it’s a bit absurd.”

Precise and mathematical, Kwade’s art reflects her affinity for philosophy and science. She studies Marx and Kant, and reads quantum physics in lieu of fiction. The Hirshhorn museum's chief curator Stéphane Aquin describes her as “an amateur historian of science.” Kwade’s curiosities are reflected in her work, which tends to pose hard questions about our relationship to objects and the universe, while creating a space for the viewer to ponder the answer.

“It’s about thinking how we describe the world, how we define objects—where they end and where they begin and what the transformations of them could be,” Kwade says. “But not just physical transformation or chemical transformation, but also the philosophical or social transformation.”

To walk around Kwade’s large-scale installation WeltenLinie, meaning “world lines,” is like passing into some strange new dimension. The visually immersive, steel-frame structure is a recent acquisition to the collections of the Smithsonian’s Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden and is now on view in the exhibition, “Feel the Sun in Your Mouth.”

For this show, assistant curator Betsy Johnson united works acquired by the Hirshhorn over the past five years. The exhibition mixes pieces from the 1960s and 70s with recent works. They hail from a dozen different countries and bring fresh light to contemporary issues. The museum says the show aims to “[harness] metaphor and suggestion to create meanings that exist outside language.”

Jesper Just’s Sirens of Chrome is a suspenseful, dialogue-free video that follows several women through the streets of Detroit. Japanese artists Eikoh Hosoe, Minoru Hirata, Miyako Ishiuchi, Koji Enokura and Takashi Arai show moody photographs depicting postwar Japan. Laure Prouvost’s Swallow and works by Katherine Bernhardt and Jill Mulleady burst with color and sensation.

By contrast, Kwade’s installation is neat and serene. Set in an all-white room and accompanied by Tatiana Trouvé’s similarly large-scale and unassuming Les Indéfinis, WeltenLinie feels accessible, yet enigmatic.

Tree trunks made in varying sizes and constructed of plaster, copper and aluminum create an eclectic kind of forest. Large metal rods frame double-sided mirrors and plain air, at times splicing differently colored tree trunks and playing tricks with the mind. The trees seem to move with the viewer, disappearing at the edge of one frame only to reappear when passing before the next reflective surface. In this space, Kwade encourages the viewer to forget the forest for the trees.

“What is defining a tree? What can I know about this tree?” Kwade said in a conversation with Aquin last week. “I can know all of its chemical structure, I can know that it’s growing, but what is our way to describe it? And what could it be like seeing it from the other side?”

Kwade was born in Communist Poland in 1979 and escaped with her family to West Germany at 8 years old. Though she doesn’t seek to make art about her experiences on both sides of the Iron Curtain, she concedes they informed her perception of differing political and social structures from a young age.

“I was raised in a completely different parallel world. This was a very different normality which then immediately was changed to another one,” Kwade says. “I was the last generation to experience both these systems.”

Her art frequently includes mirrors, allowing an object seen on one side of a barrier to be completely transformed when viewed from the other. She says she wants viewers to consider the many possibilities for a single, seemingly common object.

Once Kwade has conceptualized a piece, she scans the central objects. She then digitally manipulates them, smoothing out the bark of a tree or removing its limbs, in the case of WeltenLinie . On her computer, Kwade develops models of the finished project, virtually inspecting it from every angle. Once complete, she passes her instructions along to the production team, which builds the sculptures.

“I am satisfied if I have found the clearest way to express what I want to express,” Kwade says. “Everybody can see it is what it is.”

For WeltenLinie , Kwade duplicated her computer-generated version of the tree using plaster, copper and aluminum. She says she selected materials humans use “to build our own reality” to probe the relationships between nature and industry.

This conceptual line can be traced throughout her work. In ParaPivot, currently on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Kwade sets planet-like stones into metal frames that evoke the systems and structures we assemble to make sense of the universe. In other works, she transforms functional objects like her phone, computer and bicycle into new objects by pulverizing, twisting or otherwise re-constructing them. In everything she creates, one detects a mathematician’s precision and a poet’s insight.

“Feel the Sun in Your Mouth” is on view at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden until February 23, 2020.

Smithsonian Releases 2.8 Million Images Into Public Domain

Culture connoisseurs, rejoice: The Smithsonian Institution is inviting the world to engage with its vast repository of resources like never before.

For the first time in its 174-year history, the Smithsonian has released 2.8 million high-resolution two- and three-dimensional images from across its collections onto an open access online platform for patrons to peruse and download free of charge. Featuring data and material from all 19 Smithsonian museums, nine research centers, libraries, archives and the National Zoo, the new digital depot encourages the public to not just view its contents, but use, reuse and transform them into just about anything they choose—be it a postcard, a beer koozie or a pair of bootie shorts.

And this gargantuan data dump is just the beginning. Throughout the rest of 2020, the Smithsonian will be rolling out another 200,000 or so images, with more to come as the Institution continues to digitize its collection of 155 million items and counting .

“Being a relevant source for people who are learning around the world is key to our mission,” says Effie Kapsalis , who is heading up the effort as the Smithsonian’s senior digital program officer. “We can’t imagine what people are going to do with the collections. We’re prepared to be surprised.”

The database’s launch also marks the latest victory for a growing global effort to migrate museum collections into the public domain. Nearly 200 other institutions worldwide—including Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum , New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Art Institute of Chicago —have made similar moves to digitize and liberate their masterworks in recent years. But the scale of the Smithsonian’s release is “unprecedented” in both depth and breadth, says Simon Tanner , an expert in digital cultural heritage at King’s College London.

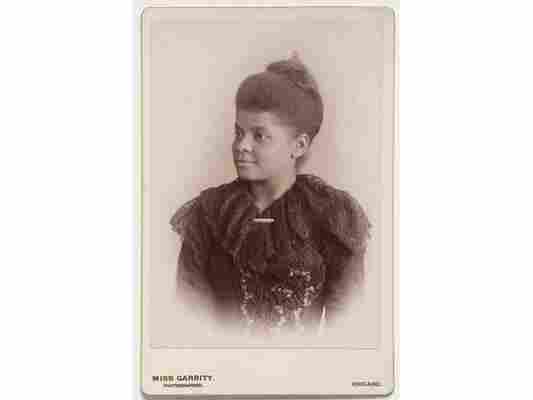

Spanning the arts and humanities to science and engineering, the release compiles artifacts, specimens and datasets from an array of fields onto a single online platform. Noteworthy additions include portraits of Pocahontas and Ida B. Wells , images of Muhammad Ali’s boxing headgear and Amelia Earhart’s record-shattering Lockheed Vega 5B , along with thousands of 3-D models that range in size from a petite Embreea orchid just a few centimeters in length to the Cassiopeia A supernova remnant , estimated at about 29 light-years across.

“The sheer scale of this interdisciplinary dataset is astonishing,” says Tanner, who advised Smithsonian’s open access initiative. “It opens up a much wider scope of content that crosses science and culture, space and time, in a way that no other collection out there has done, or could possibly even do. This is a staggering contribution to human knowledge.”

Until recently, the Smithsonian was among the thousands of museums and cultural centers around the world that still retained the rights to high-quality digital versions of their artworks, releasing them only upon request for personal or educational purposes and forbidding commercialization. The reluctance is often justified . Institutions may be beholden to copyrights, for instance, or worry that ceding control over certain works could lead to their exploitation or forgery, or sully their reputation through sheer overuse.

Still, Kapsalis thinks the benefits of the Smithsonian’s public push , which falls in line with the Institution’s new digital-first strategy , will far outweigh the potential downsides. “Bad actors will still do bad,” she says. “We’re empowering good actors to do good.”

One of the most tangible perks, Tanner says, is a “massive increase” in the scale of the public’s interaction with the Smithsonian—something that will maintain and boost the organization’s already substantial cultural cachet for audiences old and new, especially as content trickles onto open knowledge platforms like Wikipedia. “As soon as you open the collections up, it’s transformative,” he says.

Most of the change, however, will happen far beyond the Smithsonian’s walls. Listed under a Creative Commons Zero (CC0) license, the 2.8 million images in the new database are now liberated from all restrictions, copyright or otherwise, enabling anyone with a decent Internet connection to build on them as raw materials—and ultimately participate in their evolution.

“Digitizing the knowledge that’s held [at the Smithsonian] to access and reuse transfers a lot of the power to the public,” says Andrea Wallace , an expert in cultural heritage law at the University of Exeter. People are now free to interact with these images, she says, “according to their own ideas, their own parameters, their own inspirations,” completely unencumbered.

To showcase a few of the countless spin-offs that access to the collections might generate, the Smithsonian invited artists, educators and researchers for a sneak peak into the archives, and will be featuring some of their creations at a launch event set to take place this evening.

Among them is a series of sculptures crafted by artist Amy Karle , depicting the National Museum of Natural History’s 66-million-year-old triceratops, Hatcher. Karle, who specializes in 3-D artworks that highlight body form and function, was keen on bringing the fossil to life in an era where modern technology has made de-extinctions of ancient species a tantalizing possibility. Six of her nine 3-D printed sculptures are intricate casts of Hatcher’s spine, each slightly “remixed” in the spirit of bioengineering.

“It’s really important to share this kind of data,” Karle says. “Otherwise it’s like having a library with all the doors closed.”

Also on deck for the evening are three Smithsonian-inspired songs produced in collaboration with the Portland-based non-profit N. M. Bodecker Foundation , which offers creative mentorship to local students. Written and recorded by Bodecker mentees, the songs will hopefully make the colossal open access collection seem approachable, says Decemberists guitarist Chris Funk , who runs a recording studio on the grounds of the Bodecker Building and mentored the songs’ production.

“Historical figures probably wouldn’t be the first thing you’d hear written in modern music,” Funk says. But his students’ creations add a contemporary pop culture twist to the tales of prominent figures like Solomon Brown , the Smithsonian’s first African American employee, and Mary Henry , daughter of the Institution’s first secretary, Joseph Henry.

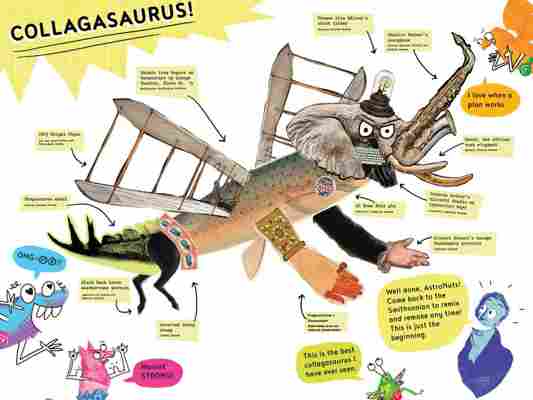

Additionally, author-illustrator duo Jon Scieszka and Steven Weinberg will debut How to Make a Collagasaurus , a how-to booklet inviting kids to transform the Smithsonian collections into zany new art forms. The approach is an echo of their 2019 children’s book, AstroNuts , which featured a cast of goofy, colorful characters pieced together from images from the Rijksmuseum’s 2013 open access launch.

In the booklet, Smithsonian founder James Smithson , backed by an entourage of AstroNuts, walks the reader through the construction of an example Collagasaurus, cobbled together from museum mainstays now in the public domain, including George Washington’s arm, a stegosaurus tail and Charlie Parker’s saxophone as an elephantine nose.

“Steven and I are perfectly built for this,” Scieszka says. “The thing I love to do is take something somebody else has, and mess it up.” The goal, he adds, is to encourage kids to do the same—and maybe even learn a thing or two along the way.

“Walking through a museum is one way you can see a work of art,” Weinberg says. “When kids make their own … that’s when you start diving deeper into a subject. They’re going to have this really rich knowledge of pieces of art.”

A bevy of research efforts are likely to flourish under the era of open access as well. In one partnership with Google, the Smithsonian has deployed machine-learning algorithms to its datasets to flesh out its list of notable women who have shaped the history of science—an effort that’s previously been aided by contributions from the public .

“Being able to see an item is a very different thing than to make another use of it,” Tanner says. “You get innovation more frequently and earlier if the knowledge people are relying on is available openly.”

With more than 150 million additional items in its archives, museums, libraries and research centers, the Smithsonian is featuring less than 2 percent of its total collections in this initial launch. Much of the rest may someday be headed for a similar fate. But Kapsalis stresses the existence of an important subset that won’t be candidates for the public domain in the foreseeable future, including location information on endangered species, exploitative images and artifacts from marginalized communities. If released, data and materials like these could imperil the livelihood, values or even survival of a vulnerable population, she explains.

“The way people have captured some cultures in the past has not always been respectful,” Kapsalis says. “We don’t feel we could ethically share [these items] as open access.” Before that can even be discussed as a possibility, she adds, the communities affected must first be consulted and be made a crucial part of the conversation.

But Kapsalis and other Smithsonian personnel also stress the importance of avoiding erasure. Many of these materials will remain available for viewing on-site at museums or even online, but the Smithsonian will retain restrictions on their use. “Representation can empower or disempower people,” says Taína Caragol , curator of painting and sculpture and Latino art and history at the National Portrait Gallery. “It can honor someone or be mocking. We are not banning access. But some things need more context, and they need a different protocol for accessing them.”

Above all, the open access initiative forges a redefined relationship between the Smithsonian and its audiences around the world, Kapsalis says. That means trust has to go both ways. But at the same time, the launch also represents a modern-day revamp of the Institution’s mission—the “increase and diffusion of knowledge,” now tailored to all that the digital age has to offer. For the first time, visitors to the Smithsonian won’t just be observers, but participants and collaborators in its legacy.

“The Smithsonian is our national collection, the people’s collection,” Funk says. “There’s something to that. To me, this [launch] is the Smithsonian saying: ‘This is your collection, to take and create with.’ That’s really empowering.”