He first appears as a crude collection of 3-D pixels—or voxels. Soon, he looks like a conglomeration of blocks morphing into the shape of an animal. Gradually, his image evolves until he becomes a sharp representation of a northern white rhino , grunting and squealing as he might in a grassy African or Asian field. There comes a moment—just a moment—when the viewer’s eyes meet his. Then, the 3-D creature vanishes, just like his sub-species, which due to human poaching is disappearing into extinction.

The Substitute , a digitally projected artwork, was produced by British artist Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg . Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum and a Dutch museum, the Cube Design Museum, commissioned the work, and Cooper Hewitt recently displayed it as part of the exhibition “Nature—Cooper Hewitt Design Triennial.” The work is now newly acquired into the Cooper Hewitt collections.

The last male northern white rhino, Sudan, died in 2018, and the two surviving females are too old to reproduce. Scientists have used sperm from Sudan and another male that died earlier to fertilize two eggs from the females, Fatu and Najin, who now reside at the Ol Pejeta Conservancy in Kenya. The hope is that the breed can be revived after the fertilized eggs are implanted in a southern white rhino to gestate.

“I just was really struck by this paradox that somehow we were getting so excited about the possibility of creating intelligence in whatever form. And yet we completely neglect the life that already exists,” says Ginsberg. “The idea that we could be able to control an A.I. to me seems kind of suspicious. We’re unable to control ourselves. . . . When it comes to killing something as extraordinary as northern white rhinos for their horns, we’re all implicated in this, even if we feel very distant.” Ginsberg also wonders what errors in reproduction may arise as humans recreate life artificially.

The Substitute reflects this uneasy paradox. Within the work’s two-minute time frame, “there’s a moment of affection and tenderness for this thing coming to life before you,” Ginsberg says. “But then it’s gone—and it’s not the real deal.” The rhino appears not on the savanna amidst woodlands or grasslands where members of its sub-species typically have grazed, but in a plain white box. Just as a lab creation would, he lacks any natural context. While a real male northern white rhinoceros weighs 5,000 pounds, this one, of course, weighs nothing. It is ephemeral, unreal.

Ginsberg, who has been trained in architecture and interactive design, is a London-based artist who often uses modern science to draw attention to questions raised by new scientific developments. Typically, her work highlights a wide spectrum of issues. Among them are conservation, artificial intelligence, biodiversity, exobiology and evolution. She was the lead author of Synthetic Aesthetics: Investigating Synthetic Biology in 2014. Synthetic Aesthetics, which is the scientific practice of redesigning living matter to make it more useful to mankind, activates passion in Ginsberg. She urges caution in these kinds of projects and illustrates her concerns with artworks that point to troubling outcomes.

“Ultimately what we saw in the exhibition was just incredibly moving,” says Cooper Hewitt curator Andrea Lipps . She describes The Substitute as “wildly successful” for communicating something both intellectually imperative but also triggering emotion, “which I think is what makes it resonate with anyone who comes in and watches it.” After seeing it herself, she realized that “it was one particular piece that everyone would talk about with everyone.”

When Lipps brought her three-year-old daughter and six-year-old son to see it, she was surprised by the differences in their reactions. Both saw a certain reality: Her daughter was frightened and confused by the authentic nature of the rhino image, but her son wanted to hug the animal.

She, too, notes the paradox. “Why are we fixated on spending resources and time and effort on de-extinction projects when . . e couldn’t keep the natural creature alive in the first place. And why would we value that kind of technological copy, if you will, more than we did the real rhino?”

Rather than bombarding viewers with facts and figures about the northern white rhino, Ginsberg believes sparking an emotional response is more effective, and thus, her artificial rhino conjures passions that a lecture would not elicit.

Like Ginsberg, Lipps questions the reality of an animal born through DNA experimentation in a laboratory far from the wild. “How much of what an animal is, do we understand to be just that information, and how much of it is much more environmental and much more contextual?” she wonders.

Over its two-minute lifetime, the faux rhino adapts “to his environment and moves around,” Lipps says. “His form and his sound become more lifelike, but ultimately, he is coming to life without any natural context and in this completely digital form. He’s totally artificial; he doesn’t really exist; and so it lends provocation and communicates with all of us about what is. Is that life?”

The rhino’s image, its sounds, and its behavior are based on 23 hours of video footage showing the last herd of northern white rhinos, which included Sudan, the last male. The video was made by a Czech scientist named Richard Policht. The rhino in The Substitute is not an exact copy of any rhino member of the herd but represents a composite image.

He acts, appears and sounds real, as any real rhino probably would. However, appearing in a sterile white box, it lacks the context and herd experience that shapes a rhino’s behavior, much as a lab-created, captive rhino would carry the proper DNA without having any of the experiences that color the life of a rhino in the wild.

Lipps believes biotechnology is “important, and it’s good that we have these explorations. But it’s also important that we just call into question what our goals and our aims are for all of it. . . . Just because we can, doesn’t mean we should. We really need to be rigorous in how we are questioning ourselves and these technologies as we continue having the ability to undertake them.”

Ginsberg encourages humans to focus on the effects of choices available in the modern world. For example, she says, “Our increasingly urban lives afford modern-day conveniences like ordering takeout in plastic containers. . . . Ask yourself: What have I excluded in that choice and did I actually care about it?” At London’s Royal College of Art, Ginsberg’s 2018 Ph.D. project, Better , explored visions of a “better” future and how they affect what designers choose to create. She argues that “better ideas” such as environmentally problematic plastic bottles and energy-saving lightbulbs, create new problems as they solve old ones. She also contends that consumers and scientists must ask better questions to reach more successful solutions. She is well-known for her lectures on these topics, and her other works include an installation, also seen at Cooper Hewitt’s Triennial that presented scents from flowers that are now extinct. This project uses gene sequences to create scented enzymes.

Her attention to the concept of “better” plays a role in The Substitute . Ginsberg raises the question of whether an artificially created rhinoceros would be better and have a greater right to live than those who preceded it and lost their lives to greedy humans.

Ginsberg has won the World Technology Award for design in 2011, the London Design Medal for Emerging Talent in 2012, and the Dezeen Changemaker Award in 2019. Twice, her work has been nominated for Designs of the Year. Her art has been displayed at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo, Beijing’s National Museum of China, Paris’s Centre Pompidou, and London’s Royal Academy of Arts, and her works are more permanently housed in museums and private collections. She has built a growing audience through lectures shared via TEDGlobal, PopTech, Design Indaba, and the New Yorker TechFest.

The Mill , which has studios in London, New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, Bangalore and Berlin, provided animation for this project, and Dr. Andrea Banino at DeepMind , an international company that develops useful forms of artificial intelligence, provided the experimental data to set the rhino’s paths. After each two-minute episode, the rhino reappears and follows another of the three programmed paths.

The Substitute is currently not on view at the Cooper Hewitt. In 2020, the artwork will be exhibited at Fact in Liverpool, with an opening on March 20 and on view through June 14, at Wood Street Galleries in Pittsburgh April 24 through June 14, 2020, and at Ark Des Stockholm , October through December.

A Great Wave of Hokusai

Katsushika Hokusai was in his 70s by the time he created his best-known image, the majestic The Great Wave off Kanagawa . Often known simply as The Great Wave, the popular print not only embodied Japanese art, but influenced a generation of artists in Europe, from Van Gogh to Monet.

Yet it was one of an estimated 30,000 images from Hokusai, who was so frenzied an artist that at one point he signed his work “Gakyō Rōji,” which translates to “the old man mad about painting.” That’s the title, too, of a new exhibition now on view at the Smithsonian’s Freer Gallery of Art.

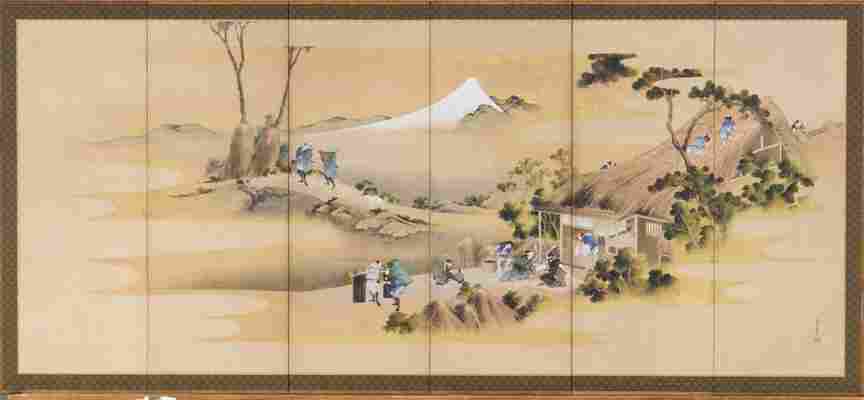

“Hokusai: Mad About Painting” brings forth from the museum’s storage vaults 120 works of art, from six-panel folding screens to rare preparatory drawings for woodblock prints. Because of their sensitivity to light, none have been on view since a hugely popular Hokusai exhibition that took place in 2006; and some so rarely seen, they were not even included in that show.

Further, because of advances in technology, some of the works are newly attributed to the influential artist, says Frank Feltens , the museum’s assistant curator of Japanese art. That includes a striking pair of dragons whose images are blown up on the walls of the hallways between the galleries, to an iconic painting of a boy playing a flute in the shadow of Mount Fuji.

The “wave” of the artist’s work at the Freer, in fact, represents the “largest collection of Hokusai paintings in the world,” says Massumeh Farhad , the Freer’s interim deputy director for collections and research.

The new show, which runs deep into next year, will mark both the 260th anniversary of Hokusai’s birth next year, and the centennial this year of the death of the museum’s founder Charles Lang Freer —the Detroit industrialist, who after amassing a collection of Asian and American art, donated it all to the United States in 1906 to create the nation’s first art museum.

“To think that Mr. Freer collected all of these more than a century ago,” says Shinsuke J. Sugiyama , the Japanese Ambassador to the United States. “All these years later, I’m amazed at his foresight and his desire to understand a part of the world that was so different from his and his deep appreciation of art that was non-Western.”

Since then, Hokusai, and in particular his Great Wave, crashed over the world, becoming one of the most recognized images in the art world. The famous work can be found on an interior page of the Japanese passport with others from the artist's Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji . It inspired Debussy and, the ambassador noted, “online, you can buy Great Wave dog bowls , Great Wave socks , or Great Wave stamps and hoodies .”

And yet, reproduced in the thousands when Great Wave was released in the early 1830s, the woodblock image is one that isn’t in the museum’s collection.

There is a variation of the theme, however, in an 1847 scroll painting, Breaking Waves —but it won’t appear until the second half of the exhibition in May. For preservation reasons, the works can only be shown for six months and must be stored away from light for five years.

The one Great Wave that does appear in the show, though, is one that won’t be widely circulated until 2024—when it appears on Japan’s ¥1,000 ($9) bill. Special accommodations by the Japan Ministry Finance allowed an enlarged reproduction of the upcoming banknote.

Hokusai is said to have disavowed any of the art that he made in the years before he turned 70. He began drawing at age 6 and worked as an apprentice to the ukiyo-e woodblock artist before he started producing his own notable work under several different names.

By his own account, it was only when Hokusai was 73, he wrote, that “I partly understood the structure of animals, birds, insects and fishes, and the life of grasses and plants.” By the time Hokusai turned 100, the artist said he hoped he would achieve “the level of the marvelous and divine,” and at his target age of 110, “each dot, each line will possess a life of its own.”

Hokusai didn’t make it that far, yet he lived and painted to the age of 90—“which of course was amazing,” Feltens says. “Ninety was a Biblical age at a time when the life expectancy was much much lower.” And the artist worked as if he knew his time was coming to a close.

“His last decade was where he was actually his most prolific,” the curator says. “He made 32 paintings alone when he was 88 and 12 in the three months when he was 90. He wanted to churn out as much as he could.”

One of those late works is a standout in the show, a sinewy, crimson colored 1847 work Thunder God. Feltens notes “the vigor of this boundless energy of this lava-like body, with red skin, a symbol of vitality and strength with the face of almost a weary old man.” Only the wavering signature belies his actual age, 88, at the time.

“The Thunder God almost looks like computer generated imagery,” the ambassador says, “A CGI effect from Hollywood. It’s really, really powerful.”

Feltens says having the works in one collection for a century—and keeping them shielded for five years at a time between viewings—ensures that the colors remain vibrant—something that surprises visiting scholars. By museum rules, the works cannot be loaned out.

It is Hokusai who is thought to have popularized the term manga —used commonly today to refer to Japanese comics—back when he published a series of books of doodles and drawing exercises. The full range of 14 volumes on display are available electronically for the first time at the Freer.

They include studies, scenes of daily life, lessons for prospective students and an unexpected manual of dance moves. “This is how you can early-19th-century Moonwalk!” Feltens says, describing the book as “outlandish and absolutely fascinating.”

It was Hokusai’s blending of traditional Japanese art, with the influence of the realism found in Western and Chinese art that made his art seem so fresh in its time, and today. Sugiyama said he hoped “the exhibit will increase interest and curiosity about Japan, especially as we go into the year that Japan will host the 2020 Olympics and Paralympics in Tokyo.”

“Hokusai: Mad About Painting” continues through November 8, 2020 at the Smithsonian’s Freer Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.

The Fierce Pride and Passion of Rhinestone Fashion

Contemporary artist Mickalene Thomas is best known for her large-scale paintings of black women posed against boldly patterned backgrounds and adorned with rhinestones. Illustrative of the artist’s signature style, her 2010 Portrait of Mnonja depicts a striking female figure reclining on a couch.

Visitors, who find their way to the high-ceiling third floor gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, consistently gather round this painting, fascinated by its bright colors and drawn to its subject—an elegant and poised African-American woman.

“She is owning and claiming her space, which is very exciting,” reveals the artist in a 2017 SAAM interview . The woman’s crossed ankles are perched on the sofa’s armrest, and her fuchsia high heels dangle over the edge. Her right hand rests on her knee and her fingers evoke a dancer’s enviable combination of strength and grace. Exuding an air of power and sophistication, Mnonja literally sparkles from head to toe—her hair, makeup, jewelry, clothes, fingernails and shoes all glisten with rhinestones.

Portrait of Mnonja is the subject of the next episode of “Re:Frame,” which sets out to investigate the connection between style and identity. What does the way we dress and present ourselves to the world say about us and inform how others see us?

Diana Baird N’Diaye , a cultural specialist and curator at the Smithsonian’s Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage, who has long studied the way that style and adornment convey identity, explains: “We dress ourselves with an aesthetic in mind, with a template in mind. It may be the community that we identify with. It may be the music we identify with. It may be where we come fromur status or the status that we aspire to… I always say that even if you wear nothing but T-shirts and jeans and you think that ‘I'm really not dressing for any reason,’ you're always dressing with some idea of your identity in mind and how you project it to others.”

A particular area of focus for N’Diaye is a project that looks at African-American dress and the aesthetics of cultural identity: “One of the major things that I think is distinctive about African-American dress is its intentionality and its agency…there are many, many aesthetics in the African-American community. There's not just one, but if you scratch the surface, they're all about what Zora Neale Hurston once called ‘the will to adorn,’ one of the most important parts of African-American expression. So it's also an art form.”

Style, identity and agency are fundamental themes in the work of Mickalene Thomas. “She’s really interested in presenting positive images of black women that explore ideas of identity and sexuality and power,” says Joanna Marsh , the museum’s head of interpretation and audience research. “She’s also really interested in ideas of style and self-fashioning.” In fact, Thomas’s connection with fashion stems, in part, from her personal biography. Her mother , Sandra Bush, was a model in New York in the 1970s and was the artist’s first muse.

Thomas’s artistic process embraces the concept of the “will to adorn.” Her work typically begins with a photo shoot. She invites her subjects, many of whom have personal relationships with the artist, “to come to her studio to dress up or get styled and then pose in a setting that she’s created... a kind of tableau or stage set, if you will,” explains Marsh. “This photo session becomes a kind of performance. Not unlike the way we all perform when we get dressed in the morning and walk out in public and are presenting ourselves to the world in a certain way.”

Thomas then takes the photographs that come out of these sessions and produces photo collages; finally, from these collages, she creates large-scale paintings using acrylic, enamel and rhinestones.

Why rhinestones? On one level, this non-traditional element is a nod to female artists who have historically used craft materials in their work and to outsider artists who use everyday objects as their medium.

But the origin story for the presence of rhinestones in Thomas’s work is also tied to economic factors. As an art student, when Thomas could not always afford traditional art supplies like expensive paint, she began purchasing relatively inexpensive materials from local craft stores: “I began going to Michael’s craft stores because I could afford felt and yarn and these little bags of rhinestones and glitter... I began to acquire these materials and find meanings and ways to use them in my own work as a way to identify myself.”

“Over time, these rhinestones became a kind of signature element of her work,” Marsh notes. Both literally and figuratively, the rhinestones add a layer to Thomas’s art: “On the most basic level, they’re a kind of decorative element. But they’re also a symbol for the way we adorn ourselves.”

In the words of the nonagenarian style icon Iris Apfel : “Fashion you can buy, but style you possess. The key to style is learning who you are... It’s about self-expression and, above all, attitude.”

One of the ways that we learn about who we are is by seeing ourselves reflected in historical and popular narratives, whether that may be a textbook, a television show, or an art exhibition.

Historically, black women have been stereotyped, marginalized, or altogether missing in these narratives. Thomas is very invested in creating a more inclusive museum environment for young people of color so that “when they are standing here…they see themselves.”

In this way, Portrait of Mnonja is both a masterful painting and a glittering example of the intentionality and agency at the heart of African-American expression.

The 2010 Portrait of Mnonja by Mickalene Thomas is on view on the third floor, east wing of the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C.