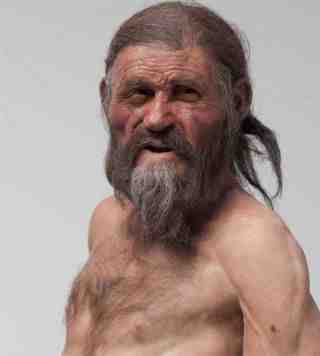

Ötzi the Iceman is the well-preserved, 5,300-year-old mummy that caused an international sensation when it was dug out of a glacier high in the Italian Alps in 1991.

Since that time, the naturally mummified individual — whom the press named Ötzi because he was found in the mountains above the Ötztal Valley — has continued to attract intense public interest and professional scrutiny as the man's mummified remains, the clothes he wore and the implements he carried have been studied over the past few decades.

Related: Frozen mammoths, bog men and tar wolves: Ways nature preserves prehistoric creatures

Indeed, Ötzi's discovery ranks as one of the greatest archaeological finds of the 20th century.

"He is so important because, for the first time, we have the possibility of knowing a Copper Age individual who died in the same situation as he had lived," said Katharina Hersel, a spokesperson for the South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology in Bolzano, Italy, where Ötzi is housed.

But the story of his discovery, as with many archaeological finds, is a tale of knowledge gained in small increments. Ötzi has yielded his secrets slowly, through patient and detailed analysis over time.

How was Ötzi found?

Ötzi the Iceman was found by two German hikers who were making their way across the Tisenjoch Pass at an elevation of 10,530 feet (3,210 meters) above the Ötztal Valley in western Austria in September 1991. The hikers were skirting a glacier on the border of Austria and Italy when they noticed the upper part of a human body protruding from the ice.

"The mummy was found lying outstretched on his stomach," Hersel said. "The left arm was strongly angled to the right and lay under the chin."

That summer had been particularly warm, Hersel said, and the high temperatures aided in exposing Ötzi's remains. "There had been a warm Sahara wind that brought sand to the glacier in which Ötzi was stuck," she said. "So it was not pure white but covered with red sand and melted even quicker."

Related: Frozen in time: 5 prehistoric creatures found trapped in ice

The German hikers alerted the Austrian authorities, who, at first, thought the body was the victim of an unfortunate mountaineering accident. This assumption prompted a hasty attempt to extract the body from the ice the following day. The rescuers, none of them trained archaeologists, tried to dig Ötzi out of the ice using axes and jackhammers. In the process, parts of the mummy — including the left hip and thigh and a few of his tools, including his bow — were damaged, Smithsonian Magazine reported .

Bad weather scuttled this first attempt to free the body from the ice, so the authorities tried again the next day. The rescue attempt took longer than anticipated, but five days after Ötzi's discovery, the mummy was freed from the ice and fully exposed.

A helicopter carried the mummy off the mountain, and the iceman was transported to the Institute of Forensic Medicine at Innsbruck Medical University in Austria. There, Konrad Spindler, an archaeologist at the University of Innsbruck, examined the remains and announced that the mummy was not a mountaineer but was "at least 4,000 years old," Scientific American reported .

The ice had preserved the body through a process of natural mummification . This process involves preserving organic tissue without the aid of human intervention, such as is the case with some ancient Egyptian mummification, or deliberately applied chemicals. In addition to extremely cold environments, natural mummification can occur in arid environments or places that are devoid of oxygen, such as bogs and swamps.

A subsequent radiocarbon analysis performed on Ötzi's tissues found that he was even older than 4,000 years. Radiocarbon dating — which measures carbon 14, an isotope, or version of carbon — determined that the iceman was about 5,300 years old, dating to 3300 B.C. This meant that Ötzi lived during the era of history known as the Copper Age, the transition period between the Neolithic, or the "New Stone Age," and the latter Bronze Age.

The Copper Age (3500 B.C. to 1700 B.C.), also known as the Chalcolithic period, represents the time when the populations of what is now Europe began to make widespread use of metals while still using stone tools but had not yet smelted copper and tin to make bronze. It was also a time when the first complex social hierarchies developed and populations began to erect large, monumental structures made of stone — the famous megalithic tombs, standing stones and dolmens of Europe.

Once excavated, Ötzi was initially housed at the Institute of Forensic Medicine at Innsbruck Medical University in Austria. But when researchers learned that the mummy had been found on the Italian side of the Alps, 100 feet (30 m) from the Austrian border, the Italian government claimed the remains, Smithsonian Magazine reported . Austria agreed, and six years later, Ötzi was transferred to the South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology. There, he is housed in a special "cold cell," which is kept at a constant 20.3 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 6.5 degrees Celsius) and can be viewed through a small window. His artifacts and clothing are also on display.

What we know about Ötzi

Since his discovery, Ötzi has undergone extensive scientific analyses, which have broadened our understanding of what Ötzi's life was like and how he died, as well as revealed more about the time period in which he lived.

The initial analyses focused on the Iceman's physical characteristics. Ötzi would have stood about 5 feet, 3 inches (1.60 m) tall and weighed around 110 pounds (50 kilograms), Live Science previously reported . From the low levels of subcutaneous fat on his body, researchers concluded that Ötzi had a lean, wiry build. An analysis of the osteons (microscopic structures in bone that are frequently used to determine the age of a skeleton) in his femur indicated that he was in his 40s when he died.

"Ötzi was fit but not completely healthy," said Hersel. Analyses demonstrated that he suffered from several ailments, including Lyme disease and intestinal parasites. Microscopic analysis of his stomach found evidence of Helicobacter pylori, a bacterium that causes stomach ulcers and gastritis, Live Science previously reported . He also has extensive wear on his teeth, and his joints — especially his hips, shoulder, knees and spine — showed signs of significant wear and tear, suggesting he suffered from arthritis . Moreover, his lungs were coated with soot, indicating that he likely spent a lot of time around open fires during his life. He even had signs of tooth decay, gum disease and dental trauma, Live Science previously reported .

DNA analyses have also untangled Ötzi's complex genome. The findings indicate that he is not related to the current populations of continental Europe but shares genetic affinity with the inhabitants of the islands of Sardinia and Corsica. A 2012 paper published in the journal Nature Communications also revealed that he probably had brown eyes, had type O blood and was lactose intolerant . His genetic predisposition shows an increased risk for coronary heart disease , which may have contributed to the development of calcifications (hardened plaques) around his carotid artery, Live Science previously reported .

Isotopic analysis, which quantifies isotopes — or different forms of the same element, such as carbon 12 and carbon 13 — was used to determine Ötzi's place of origin and reconstruct specific aspects of his diet, including what he ate before he died . Isotopes are ingested in the foods organisms eat and then stored in bones, teeth and other tissues. "Everything points to an origin from the southern side of the Alps," Hersel said.

His last meal included wild meat from ibex and red deer, cereals from einkorn wheat and — strangely enough — poisonous fern, which may have served as a "plastic wrap" to hold his food, or maybe was used as a treatment for his intestinal parasites, Live Science previously reported.

Detailed analyses of Ötzi's artifacts have also revealed much about the ancient man's life and times. Scattered bits of leather, plant fiber, animal hide, string, his ax and an unfinished bow were found near him when he was first dug out of the ice. Later archaeological excavations at the site, conducted in the fall of 1991 and the summer of 1992, uncovered additional artifacts, including more hide, leather, a knife, an arrow quiver and pieces of Ötzi's clothing. In fact, archaeologists were able to reconstruct the iceman's wardrobe , which consisted of a cloak, leggings, a belt, a loincloth, a bearskin cap and even shoes. The latter were made out of deer hide stretched on a string netting and were insulated with grass. Archaeologists also found a leather pouch containing a tinder fungus, a scraper, a boring tool, a bone awl and a flint flake.

Ötzi sported 61 tattoos, in the shape of parallel lines and crosses, that adorned his rib cage, lower back, wrists, ankles, knees and calves, Live Science previously reported . Unlike modern tattoos, these were not made with a needle; instead, fine incisions were made on his skin, and the resulting wound was filled with charcoal. Researchers do not think the tattoos were decorative; rather, they might have served a little-understood therapeutic or medical purpose, perhaps a form of primitive acupuncture .

How did Ötzi die?

Perhaps the greatest mystery surrounding Ötzi is the circumstance of his death. When he was first recovered from the ice, experts thought Ötzi was the victim of a mountaineering accident. Researchers speculated as to whether he had fallen into a crevasse, died of exposure to the elements or had simply lost his footing on the treacherous ice and tumbled to his death. However, in 2012, a detailed analysis of Ötzi's body revealed that he was likely murdered, Live Science previously reported .

Ötzi sustained two significant injuries — one to his shoulder and one to his head. The first injury consisted of a flint arrowhead embedded in his left shoulder, a detail that was picked up during an X-ray originally conducted in 2001, as reported by Scientific American . The second injury was a severe head wound, possibly from a blunt object. At first, researchers debated which injury might have caused his death. But a 2012 study published in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface revealed that the arrow was the main cause of death.

"The arrowhead pierced through the left shoulder blade and injured an important artery, the subclavian artery, under the collarbone," Hersel said.

Related: Ötzi the iceman had just sharpened his tools the day before his murder

It's possible that Ötzi bled to death within a matter of minutes, Hersel said. Moreover, the study found that his red blood cells, surprisingly intact after 5,000 years, showed traces of a clotting protein that quickly appears in human blood immediately after a wound but disappears soon after, suggesting that Ötzi didn't survive the wound.

Researchers now think that Ötzi was likely ambushed and that the arrow — shot by an unknown assailant — struck his back and killed him. It's possible that he suffered the head wound at the same time as the arrow wound or afterward, Live Science previously reported . Why he was killed, however, remains a mystery.

Three decades after his discovery, Ötzi continues to fascinate. The mummy provides a window into the life and times of an individual who lived over 5,000 years ago — a man who lived in a world far removed from our modern era of digital communications, space travel and sophisticated technologies of all kinds. Yet the clothing he wore and the tools he carried suggest he was acutely adapted to his environment and was well-versed in the plants, animals and technologies of his era. Future studies using new and innovative technologies will continue to reveal even more about Ötzi's life and times.

Additional resources