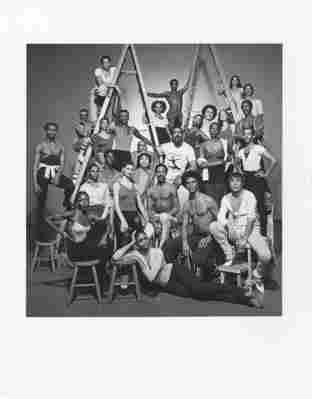

Modern dance impresario Alvin Ailey once asked photographer Jack Mitchell to shoot publicity images of his dancers for their next performance without even knowing the title of their new work. Seeing “choreography” in the images Mitchell produced , Ailey leapt into an ongoing professional relationship with Mitchell.

“I think that speaks to the trust that they had in one another,” says Rhea Combs, a curator at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture . Ailey “knew it would work out somehow, some way.”

This partnership, which began in the 1960s, led to the production of more than 10,000 memorable images, and the museum has now made those photos available online. The Jack Mitchell Photography of the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater Collection allows viewers to see 8,288 black-and-white negatives, 2,106 color slides and transparencies, and 339 black-and-white prints from private photo sessions. The collection became jointly owned by the Alvin Ailey Dance Foundation and the museum in 2013. Afterwards, the museum began the tedious effort to digitize, document and catalogue the images.

The partnership between Ailey and Mitchell was consequential for Ailey’s career: Biographer Jennifer Dunning, writes that Mitchell’s work “helped to sell the company early on.” Combs believes that is true. “Ailey was not only an amazing dancer and choreographer . . . .He had to be an entrepreneur, a businessperson,” she says. In other words, he had to market his work.

This was a partnership between two artists at the “top of their game,” Combs notes. The fact that “they found a common language through the art of dance is really a testament to the ways in which art can be used as a way of bringing together people, ideas, subjects and backgrounds . . . in a very seamless and beautiful way.”

Alvin Ailey spent the early years of his childhood in Texas before moving to Los Angeles, where he saw the Ballet Ruse de Monte Carlo perform and begin considering a career in dance. He studied modern dance with Lester Horton and became part of Horton’s dance company in 1950 at the age of 19. After Horton’s sudden death in 1953, Ailey moved to New York, where he made his Broadway debut in 1954’s House of Flowers , a musical based on a Truman Capote short story. The show boasted a wealth of African American talent, including actress and singers Pearl Bailey and Diahann Carroll .

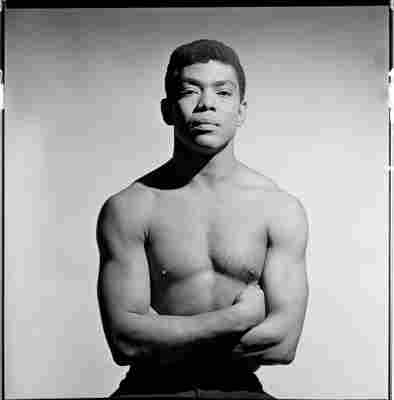

Ailey established the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater in 1958. Beginning as a dancer in his own company, he gradually diminished and eventually ceased his own performances to make more time for choreographing programs. As a New York Times reporter wrote in 1969, “four years ago, Ailey, then 34, a daring young man stepping off the flying trapeze switched from tights to tuxedo to take his opening night bow.” For Ailey, choreography was “mentally draining,” but he said that he found rewards in “creating something where before there was nothing.”

Combs says Ailey was able to create “a range of different cultural gestures in a way that was unique and powerful and evocative.”

Ailey began with a solely African American ensemble, as he set out to represent black culture in American life. “The cultural heritage of the American Negro is one of America’s richest treasures,” he wrote in one set of program notes. “From his roots as a slave, the American Negro—sometimes sorrowing, sometimes jubilant but always hopeful—has touched, illuminated, and influenced the most remote preserves of world civilization. I and my dance theater celebrate this trembling beauty.”

He highlighted the “rich heritage of African Americans within this culture,” placing that history at “the root” of America, says Combs. “He really was utilizing the dance form as a way to celebrate all of the riches and all of the traditions,” She argues that he was able to show that “through some of the pain, through some of the sorrow, we still are able to extract tremendous joy.”

Though Ailey never abandoned the goal of celebrating African American culture, he welcomed performers of other ethnicities over time. In his autobiography, Revelations , he noted, “I got flak from some black groups who resented it.” He later said , “I am trying to show the world we are all human beings, that color is not important, that what is important is the quality of our work, of a culture in which the young are not afraid to take chances and can hold onto their values and self-esteem, especially in the arts and in dance.” Combs believes Ailey was trying to reflect America’s good intentions by providing “examples of harmonious interracial experiences.”

Ailey’s most revered work was “Revelations,” which debuted in 1960. It traced the African American journey from slavery to the last half of the 2oth century and relied on the kind of church spirituals he had heard as a child. In his career, he created about 80 ballets, including works for the American Ballet Theatre, the Joffrey Ballet and the LaScala Opera Ballet.

Shortly before he died of AIDS complications in 1989, Ailey said, “No other company around [today] does what we do, requires the same range, challenges both the dancers and the audience to the same degree.” After his death, ballet star Mikhail Baryshnikov said , “He was a friend, and he had a big heart and a tremendous love of the dance. . . .His work made an important contribution to American culture.” Composer and performer Wynton Marsalis saluted Ailey, saying “he knew that African-American culture was fundamentally located in the heart of American culture and that to love one did not mean that you didn’t love the other.” Dancer Judith Jamison, who was Ailey’s star and muse for years and ultimately replaced him as choreographer, recalled , “He gave me legs until I could stand on my own as a dancer and a choreographer. He made us believe we could fly.”

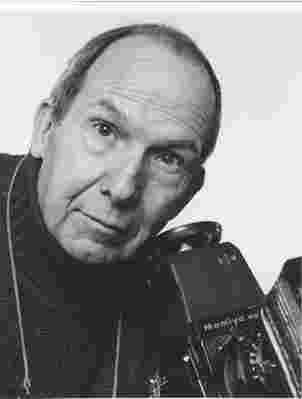

When Ailey died, Mitchell’s long career was nearing its end. His career had begun in a flash after his father gave him a camera during his adolescence. He became a professional photographer at 16, and by the time he was 24, he had begun capturing images of dancers. As he developed expertise in dance photography, he created a name for what he was seeking to capture—“moving stills.” This form of artistry “embodies the difficult nature of what he was capturing” in photos, Combs argues. Acknowledging that ballet sometimes seems to defy “the laws of physics,” she praises Mitchell’s ability “to capture that within a single frame, to allow our eyes an opportunity to gaze on again, the grace of this movement, of this motion. . . hold it in the air, in space, in time.”

By 1961 when he began working with Ailey, Mitchell said he had started “to think of photography more as a preconceived interpretation and statement than as a record.” The working partnership between Mitchell and the company lasted more than three decades.

Known for his skill in lighting, Mitchell developed a reputation for photographing celebrities, primarily in black and white. Some fans described him as someone who could provide insight into the character of his subject. He devoted 10 years to a continuing study of actress Gloria Swanson and captured a well-known image of John Lennon and Yoko Ono. Writing the foreword for Mitchell’s 1998 book, Icons and Idols , playwright Edward Albee asked, “How can Jack Mitchell see with my eye, how can he let me see, touch, even smell my experiences? Well, simply enough, he is an amazing artist.”

Mitchell retired in 1995 at 70. Over the course of his career, he accepted 5,240 assignments in black-and-white photography alone. He made no effort to count color assignments, but he created 163 cover images for Dance Magazine and filled four books with highlights of his work. He died at 88 in 2013.

In 1962, Alvin Ailey’s company began traveling the world to represent the American arts on State Department-financed tours sponsored by President John F. Kennedy’s President’s Special International Exchange Program for Cultural Presentations. By 2019, the company had performed for approximately 25 million people in 71 nations on six continents. The group’s travels included a 10-country African tour in 1967, a visit to the Soviet Union three years later, and a ground-breaking Chinese tour in 1985. Ailey’s corps of dancers has performed at the White House multiple times and at the opening ceremonies of the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City. In 2008, longtime Ailey friend and dancer Carmen de Lavallade declared that “today the name Alvin Ailey might as well be Coca-Cola; it’s known all over the world.” He became, in Combs’s words, “an international figure able to take very personal experiences of his background, his life, and his culture . . . and connect with folks all over the world.”

The work Mitchell produced in his association with the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater lives on in digital images available to the world through the museum’s website. “Their collaborative work was a tantamount example of this magic that can happen through art,” says Combs.

Viewing Iran and Its Complexities Through the Eyes of Visual Artists

The snowflakes, the ones unimpeded by the decorative umbrellas, fall on the women’s heads, sticking to their knit beanies and scarves and catching on their uncovered hair. The women’s mouths are open, as they raise their voices against Ayatollah Khomeini’s new decree. It is the last day they will be able to walk the streets of Tehran without a hijab—and they, along with 100,000 others who joined the protest, are there to be heard.

Hengemeh Golestan captured these women on film 40 years ago as a 27-year-old photographer. She and her husband Kaveh documented the women’s rights demonstrations in early March 1979. This photograph, one of several in her Witness 1979 series, encapsulates the excitement at the start of the Iranian Revolution and the optimism the women felt as they gathered to demand freedom—although their hope would later turn to disappointment. Today, Golestan says, “I still can feel the emotions and power of that time as if it were the present day. When I look at those images I can still feel the sheer power and strength of the women protesters and I believe that people can still feel the power of those women through the photos.”

Her photographs are part of the Sackler Gallery exhibition, “My Iran: Six Women Photographers,” on view through February 9, 2020. The show, which draws almost exclusively from the museum’s growing contemporary photography collection, brings Golestan together with artists Mitra Tabrizian , Newsha Tavakolian , Shadi Ghadirian , Malekeh Nayiny and Gohar Dashti to explore, as Massumeh Farhad, one of the show’s curators, says, “how these women have responded to the idea of Iran as a home, whether conceptual or physical.”

Golestan’s documentary photographs provide a stark contrast to the current way Iranian women are seen by American audiences in newspapers and on television, if they’re seen at all. There’s a tendency, Farhad points out, to think of Iranian women as voiceless and distant. But the photographs in the exhibition, she says, show the “powerful ways that women are actually addressing the world about who they are, what some of their challenges are, what their aspirations are.”

Newsha Tavakolian, born in 1981 and based in Tehran, is one photographer whose art gives voice to those in her generation. She writes , “I strive to take the invisible in Iran and make them visible to the outside world.” To create her Blank Pages of an Iranian Photo Album , she followed nine of her contemporaries and collaborated with each of them on a photo album, combining portraits and images that symbolize aspects of their lives. “My Iran” features two of these albums, including one about a woman named Somayeh, raised in a conservative town who has spent seven years pursuing a divorce from her husband and who now teaches in Tehran. Amelia Meyer, another of the show’s curators, says Somayeh’s album documents her experience “forging her own path and breaking out on her own.”

The idea of photo albums similarly fascinated the Paris-based artist Malekeh Nayiny. One of the show’s three photographers living outside of Iran, Nayiny was in the U.S. when the Revolution began and her parents insisted she stay abroad. She only returned to her home country in the 1990s after her mother passed away. As she went through old family photos, some of which included relatives she had never met or knew little about, she was inspired to update these photos to, she says, “connect to the past in a more imaginative way…[and] to have something in hand after this loss.”

Digitally manipulating them, she placed colorful backgrounds, objects and patterns around and on the images from the early 20th century of her stoic-looking grandfather and uncles. By doing this, “she is literally imprinting her own self and her own memories onto these pictures of her family,” explains Meyer. Nayiny’s other works in the show—one gallery is devoted entirely to her art—also interrogate ideas of memory, the passage of time and the loss of friends, family and home.

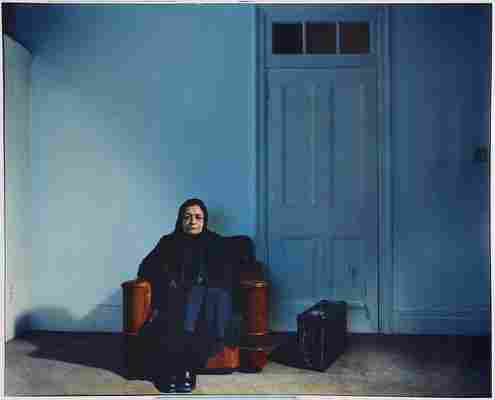

Mitra Tabrizian, who has lived in London since the mid-1980s, explores the feeling of displacement that comes from being away from one’s home country in her Border series. She works with her subjects to create cinematic stills based on their lives.

In A Long Wait , an elderly woman dressed in all black is seated on a chair next to a closed door. She stares at the camera, with a small suitcase by her side. Tabrizian keeps the location of her work ambiguous to highlight the experience of a migrant’s in-betweenness. Her works explore the feelings associated with waiting, she says, both the “futility of waiting (things may never change, certainly not in [the] near future) and a more esoteric reading of not having any ‘home’ to return to, even if things will eventually change; i the fantasy of ‘home’ is always very different from the reality of what you may encounter when you get there.”

Besides documentarian Golestan, the artists are working primarily with staged photography and using symbols and metaphors to convey their vision. And even Golestan’s historic stills take on a new depth when viewed in the aftermath of the Revolution and the context of 2019.

The “idea of metaphor and layers of meaning has always been an integral part of Persian art,” says Farhad. Whether it’s poetry, paintings or photographs, the artwork “doesn’t reveal itself right away,” she says. The layers and the details give “these images their power.” The photographs in the show command attention: They encourage viewers to keep coming back, pondering the subjects, the composition and the context.

Spending time with the photographs in the show, looking at the faces American audiences don’t often see, thinking of the voices often not heard offers a chance to learn about a different side of Iran, to offer a different view of a country that continues to dominate U.S. news cycles. Tabrizian says, “I hope the work creates enough curiosity and is open to interpretation for the audience to make up their own reading—and hopefully [to want] to know more about Iranian culture.”

“My Iran: Six Women Photographers” is on view through February 9, 2020 in the Smithsonian’s Arthur M. Sackler Gallery in Washington, D.C.

Marcel Duchamp Played With the Definition of Art and Now the Public Can, Too

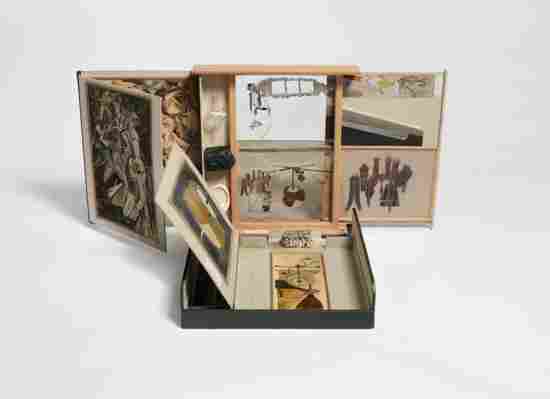

For art enthusiasts Aaron and Barbara Levine, obtaining an edition of Marcel Duchamp’s The Box in a Valise 20 years ago served as a kind of Pandora’s Box into that artist’s world.

Inside the meticulous work, with its sliding compartments and unfolding displays, were miniature representations of 68 Duchamp works over half a century. Among them are those that shook and continued to influence the art world, from Nude Descending a Staircase and The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even to his readymades and the mustache he put on a reproduction of the Mona Lisa .

Duchamp worked on the kind of greatest hits’ collection from 1935 to 1968 and described it in 1955 as a “box in which all my works would be mounted like in a small museum, a portable museum, so to speak, and here it is in this valise.”

It also became a kind of roadmap for the Levines in finding further works by the artist who died 51 years ago.

“He absolutely went crazy about it,” Barbara Levine says of her husband’s reaction to the artist behind The Box in a Valise . “It became such a major aspect of our lives. and I became totally absorbed in it also.”

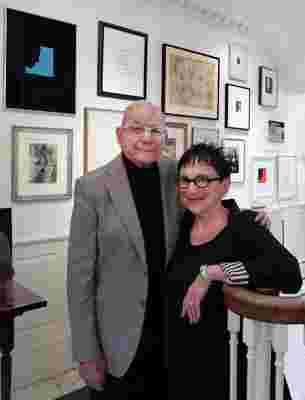

And in the intervening two decades, the couple amassed one of the most formidable private collections of Duchamp’s work, representing all parts of his career, which they have now turned into a promised gift to the Smithsonian’s Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden.

“This is a real milestone in our museum’s history,” says museum director Melissa Chiu . “This is in fact the most important donation by individual collectors since our founding gift from Mr. Hirshhorn which founded our museum in 1974.”

And now the public can see the riches of their collection with the opening of the exhibition, “Marcel Duchamp: The Barbara and Aaron Levine Collection.”

“We’re super excited about this show,” Chiu says. “This is nearly 50 works by one of the leading artists of the 20th century who has only grown in statue and importance.”

And inside the show is that inspirational box, whose full title From or by Marcel Duchamp or Rose Sélavy (The Box in a Valise), mentioning the pseudonym he often used, as on a 1921 sculpture in the show, presented in a 1964 edition, Why Not Sneeze?

If the box works as “a mini-museum,” as curator Evelyn Hankins puts it, it’s reflected in the show. “The extraordinary thing about this is that the gift encompasses the entire arc of Duchamp’s career,” Hankins says, “From an early drawing in the first gallery of his sister in Bonn from 1908 that he made as a student, to works from the 1960s right before his death.”

From that early drawing, Duchamp changed styles quickly, beginning with his furiously cubist Nude Descending a Staircase that caused a sensation at the famous 1913 New York Armory Show of modern art—and former President Theodore Roosevelt called “an explosion in a shingle factory.”

A 1936 collotype is included of that work at the Hirshhorn. And while the original The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass) cannot travel from the Philadelphia Museum of Art due to its fragility, there are “an exceptional array” of objects that relate to it, Hankins says, from early prints and sketches—to 93 miniatures of them, some of them painstakingly reproduced for another work known as The Green Box .

“Duchamp kept all these working notes when he was thinking about it. He worked on this piece when he was in Paris, when he was in Munich, when he was in New York. It was a project he thought about and worked on for many years,” she says.

Years later, he began meticulously reproducing the notes for the work and assembling them for the box, she says, “What this work makes manifest is the idea that artists’ ideas are art works in themselves. But he also challenges ideas about authenticity and originality—where is the art work? Is the art work in the mind? Is the art work in Philadelphia?”

For conservation reasons, the papers that are shown with the box will be rotated as the exhibition continues, as will the items in The Box in a Valise . And sifting through the notes, in whatever order, makes the viewer part of the presentation.

”That’s really a critical part of Duchamp’s contribution to art,” Hankins says, “this idea that the viewer is just as important in the creation of meaning as the artist himself. You can imagine what a radical idea this was in the 1920s when he proposed that.”

“It’s all about pushing art into the mind,” Aaron Levine says. “The only way you’re going to get this stuff is to think about it and absorb it and by getting into the mind of the artist.” What might otherwise look like a hat rack, or a ball of twine, or a birdcage full of marbled cubes becomes, through its isolation and presentation by an artist, art, Levine says. “It’s in your head where the art will come alive.”

And while Duchamp’s work led to the foundation of conceptual art, there were also some lovely work he made, not least of which are the curls of the hat rack that flies in the air, alongside its equally elegant shadow. Still, he thumbed his nose at how rarefied fine art had become, famously drawing a mustache on a reproduction of the Mona Lisa .

But he worked in other fields as well, creating spinning kinetic works that are on display in one room. The exhibition ends with a number of interactive opportunities of practices Duchamp enjoyed, from chess to silhouettes. A second stage of the exhibition, opening April 18, 2020, will look at the lasting impact of Duchamp on modern and contemporary artists through the holdings in the Hirshhorn’s permanent collection. That show is also curated by Hankins, who oversaw an accompanying 224-page publication.

Barbara Levine said they chose the Hirshhorn to receive their gift not only because they live in Washington, D.C., where she was a member of the board, but mostly because, as with the other Smithsonian museums, admission is free. “Hopefully there will be a lot of young people who come through here and experience Duchamp where they never would have had the chance before,” she says.

Aaron Levine says if seeing what Duchamp created triggers the imagination of a fraction of the young people who may visit after a trip to the Air and Space Museum next door, “even 10 percent,” he says, “I’ll be more than happy.”

"Marcel Duchamp: The Barbara and Aaron Levine Collection" continues through October 15, 2020 at the Smithsonian's Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C.