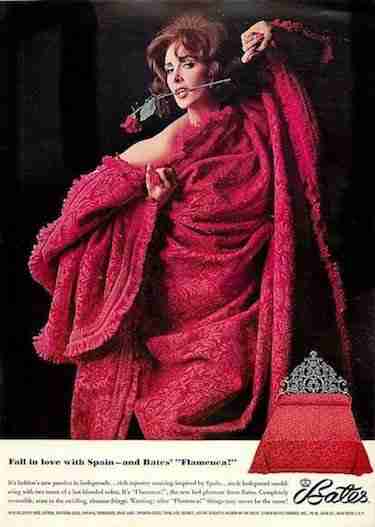

During the 1964-1965 New York World’s Fair, an advertisement for the Bates textile company in the Pavilion of Spain’s official guide book featured a fetchingly posed young woman, rose in mouth, with a ruby red bedspread draped over her body to form the likeness of a flamenco dress. The text beckons us to “fall in love with Spain—and Bates’ ‘Flamenca!’” and encourages us to discover “fashion’s new passion in bedspreads … each bedspread smoldering with two tones of a hot-blooded color.”

In the U.S. and elsewhere, flamenco is a pervasive marker of Spanish national identity. For proof of its currency in pop culture, look no further than Toy Story 3: Buzz Lightyear is mistakenly reset in “Spanish mode,” and becomes a passionate Spanish flamenco dancer. Indeed, the world outside Spain often stereotypes the nation as inhabited by flamenco dancers, singers, and guitar players who are so “passionate,” they have little time to engage in the day-to-day world of the mundane.

Inside Spain, however, the relationship between the flamenco art form and Spanish national identity has been fraught for more than a century. Indeed, the world’s love of flamenco has long created problems within Spain, where the performance was once considered a vulgar and pornographic spectacle. Over the years, many Spaniards considered flamenco a scourge of their nation, deploring it as an entertainment that lulled the masses into stupefaction and hampered Spain’s progress toward modernity. Flamenco’s shifting fortunes show how Spain’s complex national identity continues to evolve to this day.

Flamenco, which UNESCO recently recognized as part of the World’s Intangible Cultural Heritage, is a complex art form incorporating poetry, singing (cante), guitar playing (toque), dance (baile), polyrhythmic hand-clapping (palmas), and finger snapping (pitos). It often features the call and response known as jaleo, a form of “hell raising,” involving hand clapping, foot stomping, and audiences’ encouraging shouts. Nobody really knows where the term “flamenco” originated, but all agree that the art form began in southern Spain—Andalusia and Murcia—but was also shaped by musicians and performers in the Caribbean, Latin America, and Europe.

Moreover, from the mid-nineteenth century on, flamenco entertainment spread quickly from southern Spain to the capital (Madrid) and onward to other Spanish urban centers, flourishing there as a consequence of the rise of a mass urban culture and increased foreign tourism.

The reason for flamenco’s horrible reputation among Spanish elites during the 19th and 20th centuries was that historically, performances were associated with the ostracized Gypsy (Roma) population in Spain, and they took place in seedy urban areas.

Spanish elites particularly despised how foreigners linked Spain with flamenco. Spain’s national identity had previously been defined by outsiders who tied the country to Inquisitors, beggars, bandits, bullfighters, Gypsies, and flamenco dancers. Usually foreigners imposed the flamenco identity onto Spain as a backhanded compliment to highlight Spain’s steadfast authenticity. The nation had not fallen prey to the soul-sucking effects of industrialization. But with very few exceptions, Spanish elites and social reformers never liked—nor wanted—this art form to represent themselves or their nation, and they fought flamenco fever with all the resources they could muster. But flamencomania proved much more difficult to eradicate than the so-called Black Legend: the negative propaganda, spread by Spain’s French and British rivals, that characterized Spain as the land of cruel Inquisitors, sadistic colonial rulers, repressive politicians, and intellectual and artistic yokels.

Flamenco came to encapsulate Spanish elites’ feelings of shame about the country’s declining status as a great power in the modern era. Flamenco’s critics were divided into three main groups: the Catholic Church and its conservative allies, left-leaning intellectuals and politicians, and leaders from revolutionary workers’ movements. During the convulsive period between the Restoration and the beginning of the civil war, from 1875 to 1936, these groups used flamenco to critique what they saw as Spain’s political, economic, and cultural ills.

The Catholic Church perceived flamenco as an offshoot of the sort of mass cultural entertainments that led to immodesty, the breakdown of the family, and the weakening of the Patria . But for many progressive intellectuals, by contrast, flamenco—along with its twin scourge, bullfighting—was thought to keep Spaniards in a stranglehold of backwardness. They saw the entertainment as a distraction that prevented Spaniards from solving the nation’s numerous ills, including a corrupt political system, a wildly inadequate and unequal educational system, a lack of infrastructure and technological know-how, and vast inequalities of wealth. Meanwhile, for working-class reformers and revolutionaries, flamenco and its concomitant lifestyle exploited people’s poverty and diverted workers away from becoming full actors in seeking revolution to end social, political, and economic inequality.

In reality, all of these groups used flamenco as a vessel to contain their dissatisfaction with the ideological and structural changes that emerged out of the French and Industrial Revolutions. They railed in newspaper diatribes against this form of entertainment, with some critics seeing flamenco as the perverted outcome of increased secularization, while others thought it showed resistance to progress and modernization. What they were really complaining about, however, was the permeation of modern mass culture into the daily lives of everyday citizens.

The many World’s Fairs of the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries gave flamenco a boost, making Spanish Gypsy performers all the rage, especially in Paris. Flamenco “deep song” (cante jondo) received the blessings of European avant-garde artists such as Sergei Diaghilev and Claude Debussy, who had attended flamenco performances at the Paris World’s Fairs of 1889 and 1900, and found it primal and authentic. That led Spanish intellectuals and artists such as Manuel de Falla and Federico García Lorca to elevate this form of flamenco to “high culture.” Thus, the support of Europeans outside Spain transformed the cultural meaning of flamenco for Spanish artists and intellectuals in much the same way that 20th-century European support for African-American jazz and blues aided their popularity in the United States.

But after the tragedy of the Spanish Civil War, from 1936 to 1939, flamenco performances in Spain diminished considerably. The Catholic Church and leaders of the Sección Femenina (the female wing of Spain’s Fascist Party) disavowed flamenco. To counteract its perceived evils, they promoted folk dancing and singing, encouraging a new kind of national identity predicated on Spanish regional diversity and cleansed of flamenco’s torrid reputation.

But by the 1950s, after years of international isolation, the Franco regime needed money. This led the regime to change course, promoting flamenco in order to jump-start Spain’s tourist industry. A tourism promoter named Carlos González Cuesta wrote, “We have to resign ourselves touristically to be a country of [Spanish stereotypes], because the day we lose the [Spanish stereotypes], we will have lost 90 percent of our attraction for tourists.”

So the Franco regime pandered to tourists’ love of flamenco, increasing the number of clubs that specialized in it, advertising female flamenco dancers on tourism and airline brochures, encouraging professional flamenco performers to star in Hollywood films, and featuring performers in traveling exhibitions like the 1964-1965 New York World’s Fair. These strategies worked; the regime was able to bring in millions of tourists and their money to help fund Spain’s economic boom of the 1960s.

After Franco’s death in 1975, the role of flamenco once again changed dramatically. The nearly simultaneous movements for regional autonomy within Spain and the growth of a world music culture complicated flamenco’s relationship to Spanish national identity. The foreign depiction of Spain as the land of flamenco, the not-quite European country with the Oriental-Gypsy soul, has been exploited by entrepreneurial spirits within Spain. That is not to say that flamenco flourishes today only to serve the interests of commerce. Artists, scholars, and historical preservationists have chosen to undertake serious study of the art form and to promote its historical and artistic significance for both Spain and Andalusia. In fact, one could say that flamenco today has undergone both extreme commercialization and renewed artistic and academic respect, once again demonstrating its complex relationship to Spanish national identity.

Sandie Holguín is a professor of history at the University of Oklahoma. Her most recent book is Flamenco Nation: The Construction of Spanish National Identity .

Long Sidelined, Native Artists Finally Receive Their Due

Museums are beginning to rewrite the story they tell about American art, and this time, they’re including the original Americans. Traditionally, Native American art and artifacts have been exhibited alongside African and Pacific Islands art, or in an anthropology department, or even in a natural history wing, “next to the mammoths and the dinosaurs,” says Paul Chaat Smith , a curator at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI). But that has begun to change in recent years, he says, with “everyone understanding that this doesn’t really make sense.

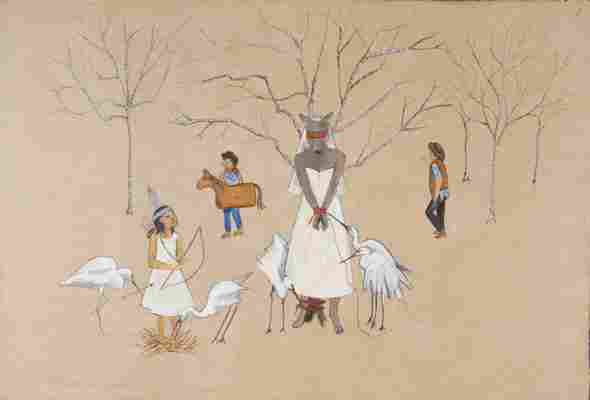

Smith is one of the curators of “Stretching the Canvas: Eight Decades of Native Painting,” a new exhibition at the NMAI’s George Gustav Heye Center in New York City. The show pushes to the foreground questions of where Native American art—and Native American artists—truly belong. The paintings, all from the museum’s own collection, range from the flat, illustrative works of Stephen Mopope and Woody Crumbo in the 1920s and ’30s to Jaune Quick-to-See Smith’s politically current Trade Canoe, Adrift from 2015, depicting a canoe overloaded with Syrian refugees. Some paintings include identifiably Native American imagery, others don’t. But almost all reveal their artists as deeply engaged with non-Native art, past and present. The artists reflect, absorb and repurpose their knowledge of American and European art movements, from Renaissance painting to Modernist abstraction and Pop .

“American Indian artists, American Indians generally speaking, were sort of positioned in the United States as a separate, segregated area of activity,” says the museum’s David Penney, another of the show’s curators. In “Stretching the Canvas,” he and his colleagues hope to show “how this community of artists is really part of the fabric of American art since the mid-20th century.”

The show opens with a room of blockbusters, a group of paintings the curators believe would hold their own on the walls of any major museum. They state the case with powerful works by Fritz Scholder , Kay WalkingStick , James Lavadour and others.

For decades, Native American art wasn’t just overlooked; it was intentionally isolated from the rest of the art world. In the first half of the 20th century, government-run schools, philanthropists and others who supported American Indian art often saw it as a path to economic self-sufficiency for the artists, and that meant preserving a traditional style—traditional at least as defined by non-Natives. At one school, for example, American Indian art students were forbidden to look at non-Indian art or even mingle with non-Indian students.

In painting in particular, Indian artists of the ’20s, ’30s and beyond were often confined to illustrations of Indians in a flat , two-dimensional style, which were easy to reproduce and sell. Native artists were also restricted in where they could exhibit their work, with just a few museums and shows open to them, which presented almost exclusively Native art.

The doors began to crack open in the ’60s and ’70s, and art education for American Indians broadened. Mario Martinez, who has two large and dynamic abstract paintings in the exhibition, cites Kandinsky and de Kooning among his major influences. He was introduced to European art history by his high school art teacher in the late ’60s, and never looked back.

Yet even now, another artist in the show, America Meredith, senses a divide between Native Americans’ art and the contemporary art world as a whole. She talks about the challenge of overcoming “resistance” from non-Native viewers. “When they see Native imagery, there’s kind of a conceptual wall that closes: ‘Oh, this isn’t for me, I’m not going to look at this,’” she says. So American Indian artists have to “entice a viewer in: ‘Come on, come on, hold my hand, look at this imagery,’” she says with a smile. Meredith’s work in the show, Benediction: John Fire Lame Deer , a portrait of a Lakota holy man, mashes up visual references to European medieval icons, the children’s book illustrator Richard Scarry , Native American Woodland style art and the Muppets. “I definitely use cartoons to entice people,” she says. “People feel safe, comfortable.”

Penney says the exhibition comes at a moment when “major museums are beginning to think about how American Indian art fits into a larger narrative of American art history.” Nine years ago the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston opened a new Art of the Americas wing that integrated Native American work with the rest of its American collections; more recently, an exhibition there put the museum’s own history of acquiring Native art under a critical microscope.

In New York, the Whitney Museum of American Art currently has a show of multimedia work by the Mohawk artist Alan Michelson, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art last year for the first time began displaying some Native American art inside its American wing (instead of with African and Oceanic arts elsewhere in the building). Later this month the Met will unveil two paintings commissioned from the Cree artist Kent Monkman. The art world as a whole, says Kathleen Ash-Milby, curator of Native American art at the Portland Art Museum, who also worked on “Stretching the Canvas,” is “reassessing what is American art.”

As an example, Paul Chaat Smith points to Jaune Quick-to-See Smith , who has been working for decades but is getting new attention at age 79. “Not because her work is different,” he says. “Because people are now able to be interested in Native artists.”

“Stretching the Canvas: Eight Decades of Native Painting” is on view at the National Museum of the American Indian, George Gustav Heye Center , One Bowling Green, New York, New York, until autumn 2021.

The Smithsonian’s Ten Splashiest New Acquisitions of 2019

If the Smithsonian really is the Nation’s Attic, as it is sometimes called, it might require a new room or two up there. Another year of acquisitions for its 19 museums and galleries, along with the National Zoo, has added to its already massive collections.

Choosing ten standout new acquisitions may mean snubbing some of the largest new additions. A nearly 30-ton carcass of a whale was undoubtedly the smelliest acquisition of 2019. And while the National Zoo waved bye bye to its beloved Giant Panda Bei Bei , other Smithsonian museums seemed to make up for the great loss. More than 120 portraits, including such renowned subjects as George Takei, Lillian Vernon, Pablo Casals and Dolores Del Rio, arrived at the National Portrait Gallery. Collectors Chuck and Pat McLure gifted 145 intricately woven Wounaan and Emberra baskets to the National Museum of the American Indian. The National Postal Museum accepted into its collections a delightfully illustrated letter from master glass artist Dale Chiluly that was sent to the Stephanie Stebich, the director of the Smithsonian American Art Museum. And then there were the 1950s watercolors of superstar Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama that weren’t exactly new acquisitions—they were recently found in the American Art Museum’s Joseph Cornell Study Center.

Clearly, the variety of acquisitions suited the varied approaches of museums that are just as varied in reflecting the riches of the nation, and the world. Our choice of notable standouts are:

Hanging not far from the 45.52 carat Hope Diamond that has long attracted lines at the National Museum of Natural History is the museum’s newest glittering gem—the 55.08-carat Kimberley Diamond . The fancy yellow diamond, a gift from philanthropist Bruce Stuart, is hailed as “one of the world’s great gemstones,” by National Gem Collection curator Jeff Post, who dubs it “a true icon.” The elegant, elongated emerald-cut diamond came from a 490-carat crystal found in the Kimberley mining region of South Africa in about 1940. Set into its current platinum necklace adorned with 80 baguette-cut diamonds weighing more than 20 carats, the Kimberley Diamond became one of the most recognizable diamonds in the world, even getting cameo appearances in TV shows like “It Takes a Thief” and “Ironside.”

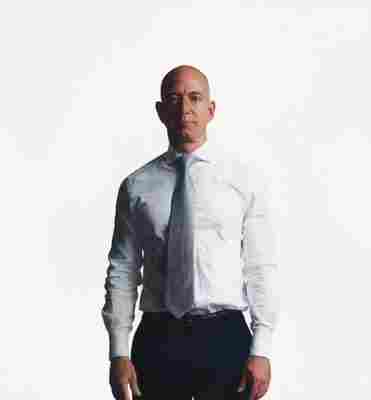

The newly unveiled rendering of Jeffrey P. Bezos by Robert McCurdy, commissioned by the National Portrait Gallery, is so realistic it has a velvet rope in front of it, lest visitors be tempted to touch, poke or maybe borrow a few grand from the Amazon founder who is also one of the richest men in the world. McCurdy, known for his hyperrealist work, spent 18 months on the painting, whose reference was a photograph. As lifelike as it looks, the portrait is literally larger than life, proven when the subject posed with it during a ceremony in November. “He’s really honored to have his portrait here,” says museum director Kim Sajet. It is one of 19 portraits of famous figures from Lin-Manuel Miranda to Anna Wintour featured in a "Recent Acquisitions" show at the Portrait Gallery running through August 30, 2020.

The 75th anniversary of D-Day, the massive Allied operation that was the turning point of World War II, was marked in part by the addition of a tattered American flag to the National Museum of American History, given by a pair of Dutch collectors in appreciation for the efforts of U.S. troops. The 30-by-57-inch, 48-star flag, discolored from dirt and diesel exhaust, flew over one of the landing crafts off Utah Beach in Normandy, France. It has at least one symmetrical hole that appears to have come from German machine-gun fire. It was presented to the Smithsonian during a July ceremony at the White House following a meeting between the U.S. president and the Netherlands prime minister. “It’s a great honor to be entrusted with this flag and share it with the American people,” says museum director Anthea M. Hartig. It joins other museum objects commemorating the anniversary of D-Day in an ongoing display .

The visual depth of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture will be greatly enhanced by the 2019 purchase of the photo archive of Ebony and Jet magazines that became available when Johnson Publishing went bankrupt. Political and cultural icons from the African American community abound in the 4 million images, including Martin Luther King, Aretha Franklin and Muhammad Ali, as well as landmark photographs such as the shocking view of the mutilated body of Emmett Till in his coffin. “The archive is a national treasure and one of tremendous importance to the telling of black history in America,” says Darren Walker of the Ford Foundation, which joined forces with the Andrew W. Mellon and John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur foundations and the J. Paul Getty Trust to purchase the archive for $30 million.

The oldest piece of art acquired by the Smithsonian in 2019 may be a Renaissance-era drawing, Men Hunting Bulls with Falcons by Jan van der Straet (1523-1605) . It’s one of a series of hunting scenes by the Flemish court artist to the Medici, who was better known as Stradanus. The Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, was already a center for the study of Stradanus with more than 300 drawings archived. Among its holdings was a preparatory sketch for the newly acquired finished drawing—one of the thousands of sketches purchased for the collection by museum founders Sarah and Eleanor Hewitt. Reuniting the finished drawing with the preliminary sketch “not only illustrates the function of the preliminary sketches, but more broadly illustrates the essential role played by drawing in the practice of design,” says Julia Siemon, assistant curator of drawings, prints & graphic design at Cooper Hewitt.

White Environ #5 by George Morrison , is a 1967 abstract painting from a respected New York abstract expressionist whose peers were Franz Kline and Willem de Kooning. It was purchased by the National Museum of American Indian because the artist was one of the first natives to shine in those circles. A Grand Portage Chippewa from Minnesota, whose native name was Wah Wah The Go Nay Ga Bo (or Standing in the Northern Lights), Morrison thought of himself as an artist who happened to be a Native American. Freed from the expectations of tribal art, he became an influence for generations after him through his both work and through teaching. The acquisition is currently in a group show, “Stretching the Canvas: Eight Decades of Native Painting” at the museum’s Heye Center in New York City on view through fall 2021.

The big rockets at the National Air and Space Museum have generally been those provided by NASA. But the museum this year acquired RocketMotorTwo , the hybrid engine that powered the privately-funded Virgin Galactic’s SpaceShipTwo, called VSS Unity—its venture into commercial spaceflight. First sent into space December 13, 2018, it joins Virgin Galactic’s SpaceShipOne in the collection. “It is a unique piece of history that represents a new era in space travel,” says museum director Ellen Stofan. The engine will be displayed in the “Future of Spaceflight” exhibition scheduled to open in 2024 as part of the museum’s seven-year renovation. Until then, the public can view it at the museum’s Udvar-Hazy Center in Chantilly, Virginia.

There is a bit of local pride in the addition at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden of two works by a leading figure in the Washington Color School artist whose hallmark Light Depth by Sam Gilliam, a sprawling, 10-by 75-foot-long piece of stained, unstretched canvas, was commissioned by the Corcoran Gallery of Art upon the occasion of its 1969 centennial as one of the first fine art galleries in the country. When the Corcoran closed in 2014, its 17,000 works went under the care of the National Gallery of Art, to be distributed to peer institutions. The Hirshhorn received more than two dozen major works from the collection in 2019 including Light Depth , and a later Gilliam work, 1994’s Level One . The 50-year-old work by Gilliam, the Mississippi artist who at 83 is one of the District’s most significant artists, is meant to change upon each installation, and will likely do so in its new locale.

Acquisition seems like a cold word to use for new additions at the Smithsonian’s National Zoological Park. Especially when considering the rare clouded leopard— the first at the Zoo—who made their debut there in September. Let’s instead call them new residents. The National Zoo has had adult clouded leopards since 2006. But Paitoon and Jillian, born last spring at the Nashville Zoo, are the first cubs. For decades, scientists at the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute have been studying behavior of clouded leopards. The wild cats from the Himalayan foothills are found through mainland Southeast Asia into southern China. They are listed as vulnerable in the wild by the International Union of Conservation of Nature, which estimated that there are about 10,000 clouded leopards in the wild.

The bright and splashy Toilet paper and cigarettes black and pink by Katherine Bernhardt is part of a current recent acquisitions show at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden. And the work by the Brooklyn artist is an arrangement of just that: Eight giant butts and 14 rolls across an 8-by 10-foot canvas. Born in 1975 in Missouri, Bernhardt, christened “the so-called female bad-boy of contemporary art,” has only been exhibiting her vivid paintings this century. Her other unexpected subject matter includes Nike swoops and Pink Panther profiles. Toilet paper… is currently on display as part of a show titled “Feel the Sun in Your Mouth: Recent Acquisitions,” named after a phrase used in the French artist Laure Prouvost’s video, Swallow, also new to the collections.