At first glance, David Levinthal ’s Iwo Jima appears to be a colorized version of the famed image that earned photographer Joe Rosenthal a Pulitzer Prize. But take a closer look, and a number of inconsistencies emerge. Not only is the orientation of Levinthal’s wartime scene reversed, but it also features an unfurled, bullet-riddled American flag and, most importantly, the six Marines raising the flag in the original image are represented by a group of toy soldiers.

This sense of familiarity, followed by the immediately unsettling realization that nothing is actually as it seems, pervades Levinthal’s oeuvre. As alluded to by the title of a new exhibition, “ American Myth & Memory: David Levinthal Photographs ,” now on view at the Smithsonian American Art Museum , the artist’s work relies on an unexpected vehicle—toys, including plastic cowboys, athletes, Barbies and pin-up models—to reveal the constructed nature of some of the foundational aspects of national identity.

The show unites 74 color photographs taken by Levinthal between 1984 and 2018. Some belong to his “History” series, which restages such well-known events as the assassination of President John F. Kennedy and George A. Custer’s last stand at the Battle of Little Bighorn, while others are extracted from the series “Modern Romance,” “American Beauties,” “Barbie,” “Wild West” and “Baseball.” All center on toys, precisely posed to serve as society's stand-ins.

By drawing on “universally recognizable” events, objects and figures, says exhibition curator Joanna Marsh , Levinthal invites viewers to bring their “own associations and memories” to photographed subjects, whether they are soldiers crossing “ No Man’s Land ” on World War I’s Western Front, a pioneer woman cradling her child, or a baseball player sliding into home base.

Moments in every culture become “mythologized over time. . . through the collective remembrance of an event and the retelling of that event by a community or a larger society,” says Marsh, who serves as the museum’s deputy education chair, head of interpretation and audience research.

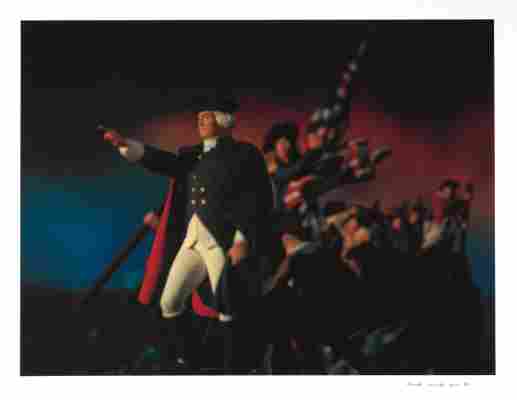

In many instances, perceptions of events are shaped by photographs, paintings or images otherwise circulated for mass consumption. George Washington’s crossing of the Delaware, for example, is cemented in popular imagination by Emanuel Leutze’s 1851 oil painting , a heroic and largely romanticized depiction of the 1776 event that was painted decades after the fact.

Levinthal’s version is similarly idealistic, portraying Washington’s progress as unimpeded by the ice and wind that actually affected the crossing. As the artist explains, this representation is “embodied in the painting, so that’s how we view it” to this day. The work’s exhibition wall text further states: “The artificiality of the figure is immediately apparent, underscoring the fiction that lies at the heart of how Americans visualize this historic event.”

Photography, meanwhile, is often viewed as a more reliable record of reality, purportedly displaying what Levinthal calls “the truth of the moment.” But just as paintings are shaped by their artist’s point-of-view, photographs are susceptible to manipulation—a fact accentuated by Levinthal’s scenarios, which are constructed wholly for the camera.

The artist’s first monograph, co-authored by Garry Trudeau of “ Doonesbury ” fame, exemplifies this tension between fantasy and fidelity. Titled Hitler Moves East: A Graphic Chronicle, 1941-43 , the 1977 book takes a journalistic approach to the Nazis’ eastward advance, placing plastic toy soldiers in sepia-toned, manufactured yet eerily realistic war zones. The artistic nature of this early series is so subtle, in fact, that a woman came up to Levinthal shortly after the work’s publication and commented , “You look awfully young to have taken these pictures during World War II.”

Around the same time as this encounter, Levinthal stopped by a bookstore and found Hitler Moves East in the history rather than art section.

“It never crossed their mind that it was an art book, which it’s now considered to be,” he says.

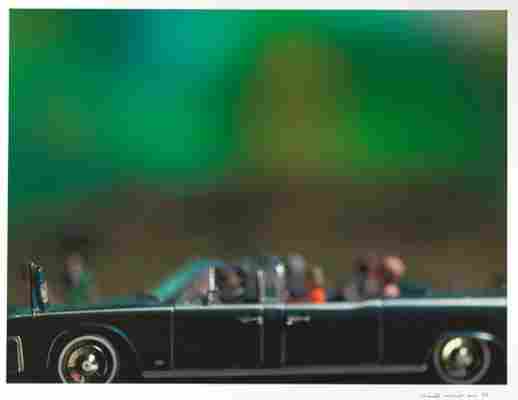

As Marsh observes, many of the photographs included in “American Myth & Memory” are surprisingly sparse. Dallas 1963 , for instance, focuses on an innocuous black car; in conjunction with the work’s title, however, the pink-suited figure in the backseat of the vehicle readily identifies the image’s subjects as Jackie and John F. Kennedy.

“When we look at that photograph, which is quite spare in its detail and very blurred,” Marsh says, “we see far more than what's actually in the photograph because we're bringing all those visual cues and associations that we have stored in our own memory.”

Some of Levinthal’s snapshots feature little beyond loose toys, a sandy landscape and a dark or spray-painted background. Others zoom in on aspects of complex dioramas—including one commissioned for the artist’s “Wagon Train” series and now installed in the exhibition. Visitors standing at one end of the migratory scene can peek through the glass case and simultaneously spot both a miniature mounted cowboy and, on the wall behind the diorama, a photograph of that same figure and his trusted steed.

For the majority of his more than 40-year career, Levinthal relied on Polaroid technology to bring his constructed scenes to life. Then, in 2008, Polaroid stopped producing the film used in its 20x24 camera, forcing the artist to make his first foray into the world of digital photography.

“ I.E.D. ,” a 2008 series on the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, was the first of Levinthal’s work to receive the digital treatment. As Marsh notes, the timing was apt: Unlike Hitler Moves East , the conflict in question was ongoing and being relayed to the public via social media, 24-hour news coverage and other instantaneous sources of information. Digital technology, therefore, not only afforded Levinthal what he describes as “total freedom of scale” and a “beautiful” working system, but also provided a medium that Marsh says “felt more appropriate to the moment.”

Mass media and the influence of memory on myth-making are central concerns throughout Levinthal’s work. As the artist once explained, his “Wild West” series represents “a West that never was, but always will be,” reflecting romanticized conceptions of cowboy culture created by television and radio shows rather than the harsh reality evident in historical accounts.

Levinthal, born in San Francisco in 1949, grew up watching Westerns. While conducting research for the “Wild West” series, however, he realized the gunslinging cowboys of his imagination “bore absolutely no relationship” to the actual westward expansion of the late 19th century. Instead of offering accurate historical perspectives, Levinthal says, depictions of the period often strive to “embellish and expand” on the legend of the Wild West.

This emphasis on perpetuating fictions rather than replicating reality is also at the heart of the artist’s “American Beauties” and “Barbie” series. Both bodies of work center on idealized versions of women who alternately evince wholesome, barely concealed sensuality and fashionable domestic refinement. “The doll becomes sort of the perfection of our visual fantasy, ” Levinthal says. “The doll is seemingly without flaws.”

Marsh argues that the series’ portrayal of idealized women underscores the role of toys, and particularly dolls, in teaching societal norms, values and assumptions from a very young age.

“They aren't just playthings,” the curator says. “They have a much weightier significance within popular culture.”

Ultimately, Levinthal’s work thrives on the tension between a number of seemingly discordant ideas: the innocence of toys versus the brutality of war, the veracity of photography versus the manipulation apparent in constructed scenes, and the memories of events versus nostalgic, mythologized narratives. As the exhibition wall text points out, the artist’s images hide “the toy-ness of his subjects,” blurring figures until they appear almost human, but the “illusion is never quite complete.”

To look at a Levinthal photograph is to acknowledge its artificiality and — in doing so — gain a deeper understanding of the flawed, often fictitious forces that continue to shape modern American identity.

“ American Myth & Memory: David Levinthal Photographs ” remains on view at the Smithsonian American Art Museum through October 14, 2019.

This Year’s Outwin Winners Challenge the Norms of Portraiture

Portraiture is due for a reframing. Although the art form has traditionally served to memorialize the affluent and the powerful, the finalists of the 2019 Outwin Boochever Portrait Competition point to a future where portraits empower the disenfranchised.

The triennial competition, founded in 2006 by an endowment from the late Virginia Outwin Boochever, calls for artists to “challenge the definition of portraiture.” First-prize winner Hugo Crosthwaite does just that. His 2018 stop-motion animation, A Portrait of Berenice Sarmiento Chávez , illustrates one woman’s journey from Tijuana, Mexico, to the United States.

“What's fascinating about the portrait is that it's not a static work of art,” says Taína Caragol, co-curator of the exhibition. The animated portrait is composed of some 1,400 photos Crosthwaite took throughout his drawing process. Based on the story of a woman the artist met in his hometown of Tijuana, the work follows Chávez on her pursuit of the American dream. Caragol says the animation includes some moments that may feel dramatized, but symbolize the struggles Chávez encountered throughout her journey.

"When she told me this story, it had a lot of fantastical elements, elements that you doubted if they were true," Crosthwaite says. "But it didn’t matter because it was her story . . . We are defined by our stories. We present the story that we tell ourselves, or that we tell others, as our portrait."

Crosthwaite adds that Berenice's journey speaks to "universal truths," like the persistent pursuit of a better life. Her story has all of the elements of an epic odyssey, he says. "You struggle to reach a goal, then you reach it and the goal might not be exactly what you wanted. And then you end up back in Tijuana, but you’re still dreaming."

Dorothy Moss, the director of the 2019 Outwin competition and co-curator of the exhibition, says immigration is among many contemporary themes that came up in this year’s more than 2,600 entries. She says the call for submissions encouraged artists to respond to “our contemporary moment,” yielding work that touched on LBGTQ rights and activism, the Black Lives Matter movement and gun violence. For the first time, this year’s rules also allowed artists to look to the past and memorialize historical figures who may not have been represented in portraiture in their lifetime.

“In this competition, you see work that is about the contemporary moment and about issues that we are all grappling with as we watch the news,” Moss says. “But we are also showing work about historical figures whose lives may be at risk of being erased if they aren't represented by artists today.”

Many of the other portrait subjects are simply ordinary people. Second-prize winner Sam Comen captures the enduring spirit of the American worker in Jesus Sera, Dishwasher (2018). The man depicted looks “proud, but also weary,” Moss notes. Another portrait, Our Lamentations: Never Forgotten Daddy (2018) by Sedrick Huckaby depicts a woman wearing a T-shirt with her late father’s face printed on the back, which is part of a series that addresses the disproportionate death rate in communities of color.

These portraits that empower the unseen represent an interesting development in the genre, Caragol says. “There is a realization by artists of how powerful a portrait can be to assert the presence and to affirm the dignity of individuals,” she says. “They present the harsh realities that many people who are vulnerable in our society face, but without victimizing the person, instead showing them as strong, resilient, holding power within.”

This year’s finalists not only challenged conventions of who sits for a portrait, but also embraced nontraditional mediums such as video and performance art. Sheldon Scott’s Portrait, number 1 man (day clean ta sun down) (2019) is the first performance art piece in the Outwin’s history. From sunrise to sunset six days a week, Scott will kneel on a piece of burlap and hull rice grown in South Carolina, where his ancestors were slaves. Visitors are encouraged to sit and meditate as they watch his methodical work, which will continue through Nov. 2.

One commended video piece, Self-Portrait (2017) by Natalia García Clark, poses a question to viewers: “How many steps can I take until I disappear from your perspective?” The artist then walks away from the camera into a barren landscape until, after six minutes, she is no longer visible to the viewer. “It’s a piece about how the measure of our existence is in relation to each other,” Caragol says.

The experimental nature of these pieces, when combined with the contemporary subject matter, conveys a sense of urgency that Moss has never seen in prior competitions. She also directed the 2013 and 2016 Outwin competitions, and she notes that artists were especially bold in their submissions this year.

Moss says the selection of portraits displayed in “The Outwin 2019: American Portraiture Today” exhibition offers an opportunity to connect with people whose lives are affected by the various issues portrayed in the artwork. “Standing in front of portraits and talking about the lived experience of others is a way to create community, to promote dialogue, and often to come to an understanding or see a different perspective,” she says. “It's a good way to come together and to feel a sense of community during a time that is divided.”

The 46 finalists’ portraits will be on display in “The Outwin 2019: American Portraiture Today” at the National Portrait Gallery Oct. 26 through Aug, 30, 2020.

This Photographer Goes to the Ends of the Earth to Capture Rarely Viewed Animals

Roie Galitz’s adventurous spirit has quite literally driven him to the ends of the earth. He has made several excursions to the Arctic archipelago of Svalbard and the ice sheets of Antarctica, as well as the snowy tundra of Norway and the wild waters of Kamchatka, Russia — all in the hopes of capturing some of the earth’s most elusive creatures.

Although the photographer hails from Tel Aviv and first fell in love with wildlife photography in the sweltering savannahs of Tanzania, Galitz says he prefers to work in the cold—even when that can mean temperatures as low as 40 degrees below zero. He layers up multiple pairs of long johns, fleece shirts and the thickest wool socks he can find. On top of all of that, he wears an eight-pound Arctic suit. “When you're cold, you can always put on an extra layer,” he says. “But when you're hot, there is a legal limit to how much you can remove.”

Extreme environments are also where he finds his favorite photography subjects: animals that are rarely viewed in the wild.

“If I showed things that have been viewed time and time again, it wouldn't be special. It wouldn't be unique,” Galitz says. “It would be just be like photographing a sparrow. Who cares about a sparrow? Everybody sees them all the time. As a photographer, I always try to find what has been done, what hasn't been done, why hasn't it been done—then try to do it.”

One photo that captures Galitz’s quest features a polar bear with a live seal in its grasp. This moment of the hunt had rarely, if ever, been photographed before, and local bear experts doubted that Galitz would be able to get the shot. But after a long night of silently kneeling on the ice, fighting to stay warm but remaining still as to not disturb the seals swimming below—he nabbed it.

Venturing into the wild comes with some risk, from frostbite to close encounters with bears and walruses, but Galitz takes it all in stride. A minor case of frostbite in the Arctic is like getting a sunburn at the beach, he says. And the cold forces him to be resourceful. On multiple occasions, he has used his nose to operate the touch screen on his camera, although sometimes he will quickly remove his gloves to snap the shot.

Wildlife photography requires a certain entrepreneurial spirit, Galitz says. For many of the far-off places he chooses to shoot, he has to obtain production permits and coordinate the often-complicated logistics of getting there. But the planning pays off, he says, when he gets the perfect shot. In a photo titled “ Polar Bear Family Hug ,” he captured two cubs and a mother bear in a moment of vulnerability as they awoke from a nap. “That's actually the best compliment a wildlife photographer can ask for,” Galitz says. “Because when an animal is sleeping in front of you, it means she trusts you.”

In another photo of brown bears playing together in Lake Kuril in Russia, Galitz laid low to the ground and took shot after shot trying to capture the symmetry of the bears’ open mouths. “With wildlife, you control the scene by controlling yourself,” he says, referring to his position in relation to his furry subjects. You can’t tell a bear to strike a pose or turn toward the light, so for a wildlife photographer, Galitz explains, it’s all about the technique.

In addition to stunning action shots, Galitz also looks to capture moments that will elicit specific feelings from the viewer. “When I'm photographing the animals, I'm trying to show their character, their soul,” he says. Many of his photos depict animals in moments of closeness—courting, parenting, cuddling—to demonstrate their individual personalities and familial relationships. “I'm trying to make people relate to animals in an intimate way, as I am relating to animals in an intimate way,” he says.

Galitz, an official Greenpeace ambassador since 2016, regularly uses his photography to promote conservation efforts. Looking at his photos from year to year, he says he can see the world changing and the habitats of the animals he photographs disappearing. “My images are testimony,” he says. “This is what I saw last year, this is what I saw here, you can see the difference. We can't ignore that.”