In 1996 David Irving, a British writer known in certain circles for his expertise on Nazi Germany, sued Deborah Lipstadt, a historian and professor at Emory University, for libel because she called him “one of the most dangerous spokespersons for Holocaust denial.” Irving—who has asserted unequivocally and wrongly that ''there were never any gas chambers at Auschwitz”—strategically filed the lawsuit in the U.K. By law, the burden of proof for libel cases in that country lies with the defendant, meaning he knew that Lipstadt would have to prove he had knowingly promoted a conspiracy theory.

Lipstadt didn’t back down. A lengthy court battle ensued, and four years later, the British High Court of Justice ruled in her favor.

What the trial (later dramatized in the film Denial starring Rachel Weisz) ultimately came down to was a trove of irrefutable documentary evidence, including letters, orders, blueprints and building contractor documents that proved without a doubt the methodological planning, building and operating of the death camp at Auschwitz.

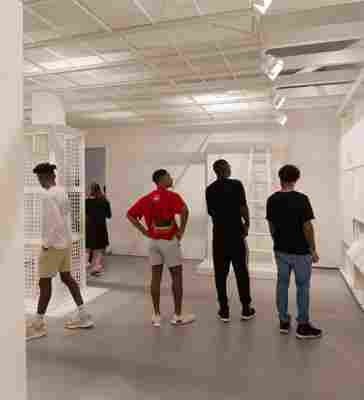

This past summer, The Evidence Room , an installation of 65 plaster casts that manifests a physical, sculptural representation of that trial, came to the United States for the first time, and went on view in the nation’s capital. Those familiar with Washington, D.C., might assume the exhibition was installed at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Instead, it went on view just a short walk down the street at the Smithsonian’s Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, where crowds jostled to see it on its short June to September showing.

“It really opens it up in a whole different way,” says Betsy Johnson, an assistant curator at the Hirshhorn. “You had people coming to see it here in the context of an art museum, who are very different than your populations at a history museum, or at a Holocaust museum.”

The Evidence Room was originally created as a piece of forensic architecture for the 2016 Venice Architecture Biennale. Working through 1,000 pages of testimony, Robert Jan van Pelt, an architectural historian and the main expert witness for Lipstadt’s case, and a team from the University of Waterloo School of Architecture led by Donald McKay and Anne Bordeleau with architecture and design curator Sascha Hastings teased out the concept of The Evidence Room from the pieces of court evidence themselves.

Everything in the work is unrelentingly white. Three life-size “monuments” are featured. They include a gas chamber door showing that its hinges had been moved because it was determined that if the door opened outward, more bodies could be put in the room. (The door was originally designed to swung inward, but it couldn’t open if too many of the dead were pressed against it.) There’s an early model gas hatch, which is how the SS guards introduced the cyanide-based Zyklon-B poison into the gas chamber. A gas column, which made the killings as efficient as possible, is also depicted. Plaster casts of archival drawings, photographs, blueprints and documents on Nazi letterheads populate the room as well. They are given a three-dimensional aspect thanks to a laser engraving technique and testify to how workers during World War II—carpenters, cement manufacturers, electricians, architects and the like—assisted in creating the most efficient Nazi killing machine possible.

Strong reception to The Evidence Room helped the architects to raise funds to return the work to Waterloo. From there, it was shown at Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, which is where Johnson first experienced it when she was sent there about a year ago by the Hirshhorn’s director and chief curator.

“I went there, and realized almost immediately that even though it hadn't been displayed in an art context before” says Johnson, “that it had potential for fitting into an art context.” Johnson recognized in the work connections with the direction that contemporary art has gone in the past four or five decades, a trend that places more importance on the idea behind the art object itself. "Really when it came down to it, even though it’s not a traditional art project, it fits so well within the trends that have been happening in the realm of contemporary art from the 1960s on,” she says.

But bringing it to the Hirshhorn meant considering the piece differently than how it had been framed before. “We realized fairly early on that there were certain ways that [Royal Ontario Museum] had framed the story that were different than the ways we did,” she says. “Things like the materiality of the work, which while they did discuss this at the Royal Ontario Museum became even more the focus in our museum,” she says. “The plaster was one that was actually quite symbolic for [the creators],” she says. “They were thinking it through on multiple different levels.”

Because this wasn’t a history museum, they also decided to go more minimalist with the text. “We still wanted people to be able to access the information about it,” says Johnson. “But we also wanted them to have this experience of confronting an object that that they don't quite understand at first.”

Asking the audience to do the work to engage with what they were seeing on their own, she felt, was key. “That work is really important work,” Johnson says. “Especially within the space of this exhibition. We felt like there's something kind of sacred about [it]. We didn't want people to be mediating the space through their phones or through a map that they hold in their hand.” Instead, they relied more on the gallery guides like Nancy Hirshbein to supplement the experience.

Hirshbein says the most frequent question from visitors was: “Why is it all white?”

“That was the number one question,” she says. “Visitors would stop. As soon as they walked in, you can tell that they were struck by the space. And I would approach them and ask if they had any questions. And then I would often prompt and say: ‘If you're wondering about anything, if you're wondering about why the room may be all white, please let me know.’” That opened up the conversation to discuss the materiality of the white plaster, and what it may have meant to the architects who designed the room.

“I would also like to find out from the visitors their interpretation,” says Hirshbein. “We sometimes did some free association, about how it felt to them to be in this very minimal white space.”

By design, the all-white nature of the panels made them difficult to read. So, visitors often needed to spend time squinting or navigating their own body in order to better read the text or see the image. “Sometimes,” says Hirshbein, “visitors intuited that. They would say things like: ‘Oh, this is difficult to read,’ and then look at me and go: ‘Oh, because it's difficult material.’”

That’s just one thing that could be pulled from that. “We're also looking through a backward lens of history,” as Hirshbein says, “and the further we get away from these things, the more difficult they are to see. That's the nature of history.” Alan Ginsberg, who serves as the director of the Evidence Room Foundation, the custodian of the work, mentions during our conversation that for him, he notices in different light, coming from different angles, that the shadows the plaster casts stand out. “It allows history to be recovered,” he says. “It allows memory to be recovered.” What you're left to do, as the viewer then, “is to understand and try to grapple with what is absent from there.”

Ginsberg says the Evidence Room Foundation, which partnered with the Hirshhorn on the exhibition, was fully on board with how the Hirshhorn framed the work. “The Hirshhorn was the obvious and perfect and premier place for this debut not only in the United States, but in the world of art,” he says. Like many people, he sees the room embodying many identities, including being a work of contemporary art.

Holocaust art has always been a controversial topic, something that Ginsberg is very aware of when he talks about the room as art. “Can you represent the Holocaust through art without being obscene?” he asks. “This is a question that has been debated endlessly. And I think the answer clearly comes down to—it depends on the specific work. There are works of art that are understood to be commemorative, or educational, or evocative, in a way that is respectful. And that's what The Evidence Room is.” Still, he says, there's something in the work and the way it’s crafted that does give him pause. “Is it wrong to have something that refers back to atrocities and yet the representation has a certain eerie beauty to it? These are good questions to ask,” he says. “And they're not meant to be resolved. Ultimately, they're meant to create that artistic tension that provokes conversation and awareness.”

The Evidence Room Foundation, which only launched just this year, is looking to use the work as a teaching tool and a conversation starter. Currently, Ginsberg says, they’re speaking with art museums, history museums, university campuses and other kinds of institutions, and fielding inquiries and requests about where to exhibit The Evidence Room in the future. For now, he’ll only say, “Our hope is that we will get a new venue announced and put in place before the year ends.”

John Singer Sargent ‘Abhorred’ Making His Lavish Portraits, So He Took Up Charcoal to Get the Job Done

John Singer Sargent became one of the most sought-after artists at the turn of the last century. Commissions rose for his lavish oil portraits but, as he wrote to a friend in 1907, “I abhor and abjure them and hope to never do another, especially of the Upper Classes.”

So at the age of 51, he took early retirement from oil portraits, says the art historian and distant Sargent relative Richard Ormond —“which is an extraordinary thing for an artist to do at the height of his powers.”

The talented artist, who was born in Florence to American parents in 1856, trained in Paris and lived most his life in Europe, wanted to devote more time to landscapes, travel and completing the murals he began at the Boston Public Library . “He wanted the freedom to paint his own things,” says Ormond, a dapper Brit in pinstripes. “But he couldn’t escape entirely.”

To satisfy lingering commissions and delight his friends, Sargent made his portraits in charcoal—a medium that allowed completion in less than three hours rather than the weeks or months his full-length oil portraits took. The works on paper showed all the facility of the psychologically informed and carefully drafted oils, but with a dash of the spontaneity charcoal gave him.

Ormond, 81, the former director of the National Maritime Museum in London and deputy director of the National Portrait Gallery there, is a renowned authority on his great-uncle, having produced a comprehensive nine-volume survey of his paintings.

Once those were complete, “I decided to start in on the portrait charcoals, which are little known because they’re all scattered in private collections,” he says. “Museums that have rarely shown them, exhibitions occasionally include the odd one or two.” Yet there are about 750 in existence.

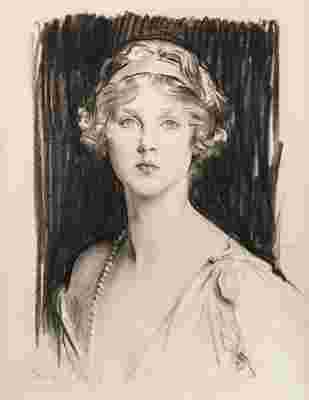

Ormond was the guest curator of the exhibition “ John Singer Sargent: Portraits in Charcoal ” held at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery in 2020—the first such drawing show in more than 50 years. The exhibition offered a rare opportunity to view 50 of the portraits, many that hadn’t never been seen in public previously. “They came from private collections,” says the museum’s director Kim Sajet. “One of the most esteemed in fact being Queen Elizabeth herself from England. She lent a number of pictures.”

A private family picture was included—a 1923 profile of the Queen Mother, from the period when she was known as Lady Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon. “Sargent made the drawing the year she was married,” says Robyn Asleson , the museum’s curator of prints and drawings who helped to organize the show. “The crown didn’t know her brother-in-law would abdicate and she would become queen eventually.”

Also lent from the Palace is a portrait of the writer Henry James, a great friend of Sargent. “They met in Paris in 1884 and James, who is a little over a decade older than Sargent, became his great champion,” Asleson says. “Through his art criticism and writings, he really pushed Sargent’s career and was the one who urged Sargent to move from Paris to London, where he thought he’d have a good market.”

The James portrait was commissioned by the writer Edith Wharton, who, like Sargent, was dissatisfied with the result (“I think that points to the difficulties when you know someone so well, and you try to make a portrait of them and it’s impossible to encompass all you think and feel and know about him,” Asleson says). Sargent instead presented it to King George V in 1916, two weeks after James’s death at 72.

Like James, Sargent was seen as a major transitory figure between the traditional and modern worlds. His charcoals are faithful to the kind of sharply-observed psychological insights that would inform his oils, but also display a kind of freehand spontaneity, particularly in the vividly drawn backgrounds that make them a harbinger of more expressive things to come.

The exhibition was organized by the Portrait Gallery with the Morgan Library & Museum in New York, where it showed late last year in its ornate hallways.

“It felt very Victorian,” Asleson says of the Morgan’s presentation. “Our designers wanted to do something totally different so it’s not the same show, but also to convey this idea of modernity and freshness and lightness and spontaneity.”

The resulting yellows, peaches and baby blues on the walls, she says, “are quite different than anything I’ve seen with Sargent.”

“Because we’re a history museum we really have to make a case for the people we show, that they’re worth remembering, they’re important,” Asleson adds. “So, there is quite an emphasis in the labels on why they matter.”

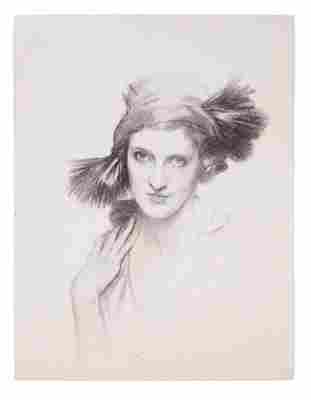

The portraits are roughly arranged in various categories or interests. And most are notable. A hallway featuring performers of the era includes a 1903 view of a vivacious, long-necked Ethel Barrymore that may have some family resemblance to descendants, such as the contemporary actress Drew Barrymore.

Sargent advised another actress to discard an earlier charcoal portrait he’d done of her once he saw her perform in one of her famous one-woman shows. The brooding Ruth Draper as a Dalmatian Peasant shows all the pensiveness of her character. The result speaks to how his personal knowledge and interaction with a subject to really get at their core helped inform the resulting portrait, Asleson says.

Sargent often made such drawings as gifts to their subjects, and signed them elaborately, “as a way of almost working off indebtedness to them for inspiring them or entertaining him or moving him,” Asleson says.

After seeing Barrymore perform in 1903, the artist wrote her a fan letter, “I would like to do a drawing of you, and I would be so honored to present you with the drawing afterward,” Sargent wrote. In the resulting portrait, Asleson says, “you see he’s almost dazzled by her star power and the limelight and the glamor.”

The highlights in the hair, often created by erasing the charcoal with bits of bread, show “he’s very good at the wavy hair,” Ormond says. “The fluency you see in his oil paints is equally true of his charcoals,” he says of Sargent. “He’s absolutely on it.”

But sitting for Sargent even for a few hours might have been “rather intimidating” for the subjects, Ormond says. “Someone would turn up in a new dress especially chosen for the occasion and he’d say, ‘I don’t want that,’” he says. “He stage-managed it, and he expected other people to play their part. The subjects, no matter how famous they were, were there to create a good figure to express themselves, so he could capture them,” he says.

“Sometimes, with some of the sitters, they were like rabbits in the headlights,” Ormond says. “‘No, that’s no good! You have to stand your ground,’ Sargent said to them. He expects an interaction, and we in a way are in the position of the artist, responding to these sitters and they’re playing their part … so it’s not passive,” he says.

The artist would charge around and make his marks, curse a mistake, or sit down to the piano to break the tension, Ormond says. “But he had those two hours to capture the essence of the person in the drawing.”

A gallery of literary figures features the James, but also a straight on view of Kenneth Grahame, author of The Wind in the Willows, and a glamour shot of W.B. Yeats commissioned as the frontispiece for the first volume of his Collected Poems in 1908 that the poet called “very flattering.”

A room of political forces has both the future Queen Mother and the future Prime Minister Winston Churchill, 15 years earlier when he was Chancellor of the Exchequer. The 1925 drawing of Churchill was one of the last works Sargent produced.

A room dedicated to artists and patrons includes a decimated Sir William Blake Richmond from 1901 and a rare 1902 Double Self-Portrait. “He didn’t like recording himself,” Ormond says of his great-uncle. “He was a private man. He liked doing other people, but didn’t like putting the searchlight on himself.”

Because the mostly larger-than-life 24- by 18-inch portraits are on paper, the Sargent show will be shorter than usual, just three months, because of the fragility of the material. Also, Sajet says, those who lent their pieces from private collections will be anxious for their return. “These have come out of people’s homes—or palaces in that case,” she says, “and they would like them back.”

The Painstaking Art of Ice Carving

The ice used at the World Ice Art Championships in Fairbanks, Alaska, is often referred to as the “Arctic diamond,” and for good reason. Thick, crystal clear and glistening with a slight tinge of aquamarine, its gemlike qualities have garnered the attention of ice sculptors from around the world who make the annual trek to east-central Alaska to test their skills carving it into intricate swordfish, dragons, polar bears and anything else that sparks the imagination.

The high-quality ice comes from a pond near North Pole, Alaska, located just southeast of Tanana Valley State Fairgrounds, where the annual competition is held. On average, volunteers from Ice Alaska, the organization responsible for executing the championships, harvest more than 4 million pounds of ice in preparation for the event, which has been taking place since 1990 and is one of the largest events of its kind in the world. Last year alone, more than 11,000 spectators came to watch as nearly 100 artists sawed and chiseled blocks of ice into gallery-worthy masterpieces.

“[The ice] is so clear that you can read newsprint through a 30-inch thick ice block,” says Heather Brice, a local ice sculptor and multi-time world championship winner.

While ice is the star of the show during the multi-week event (this year’s is scheduled for February 15 through March 31), the creativity and talent of the artists elevate it from a giant ice cube to a crown jewel.

Many of the sculptors have built their careers around ice carving, including Brice and her husband Steve, who combined have won 26 awards at the world championships. (They are also the artists responsible for the sculptures at the year-round, 25-degree Aurora Ice Museum , located 60 miles outside Fairbanks.) When they’re not competing or working on commissioned pieces, they run a successful online shop that sells ice carving tools of their own design.

“They’re the leaders in their field,” says Heather Taggard, project and volunteer coordinator for the World Ice Art Championships. “They’re so talented in what they create as well as innovative in creating tools. If they don’t have a certain burr or bit, they’ll fabricate their own.”

Some years the couple will join forces and compete together in either the two-person or multi-block classic categories, where teams receive either two or nine 6-foot-by-4-foot ice blocks, respectively, each with a thickness of between 26 and 35 inches. Other times they’ll compete against each other in the one-person classic category where each sculptor receives a single ice block. Their most recent win as a team was in 2017 with an ode to the Mad Hatter's tea party from Alice in Wonderland called "March Madness."

A panel of judges—all artists themselves—select the winners in each of the three categories who then walk away with cash prizes of up to $8,000, a welcome reward considering how much time and effort goes into creating a single piece. (Depending on the event, artists have between three and six days to finish their creations.)

“It’s not uncommon for us to work 15 to 18 hours a day to create a piece,” Brice says. “We start planning our designs a year in advance. A lot of our ideas are conceptual and we’ll draw them out and then make paper templates that are built to size. We like to be prepared and have our proportions right before we start to carve.”

As Brice describes it, "some of the pieces take design engineering to pull off." For example, last year she and her teammate Steve Dean created a piece called "Kaktovik Carcass" that entailed carving a towering rib bone of a whale balancing a raven on top. Long, thin carvings are particularly vulnerable to melting and cracking, and require a delicate touch to create.

While the World Ice Art Championships have happened for the past 30 years, the history of ice carving in Fairbanks extends further back, to the 1930s when the local community would hold an annual ice carnival and parade as a way to make the most out of the long, cold months.

“[Back then locals] would build much less refined sculptures, like a stage and ice thrones to use during the crowning of the festival’s king and queen,” Taggard says. “It made sense that years later we would have an ice carving championship, since we spend so much time in winter. We celebrate winter by celebrating ice.”

Over the years, the championships have grown in size, with more and more manpower necessary to execute the event. In the weeks leading up to the championships, artists and volunteers participate in the Ice Alaska Bootcamp , to help harvest the ice from the local pond, transport each 3,500-pound block to Ice Art Park, and build the event’s icy stage, as well as slides and an ice rink. It’s not uncommon for artists from as far away as Russia and Japan to arrive early to get to experience the world-renowned ice before the competition even begins.

“We offer some of the biggest and thickest ice [in the world],” Taggard says. “At similar events in the lower 48, artists have to work with smaller blocks of ice and do the carving inside freezers [since the outside temperature isn’t cold enough], so they’re excited to compete here outside, underneath the night sky amongst the trees.”

Working with a medium as fickle as ice is admirable, but so too is the amount of effort artists put into sculptures that will inevitably melt.

"They're a lot like sand sculptors, since they give their all to an art form that melts and slips away," Taggard says. "They're not only talented in their creations, but they need to have endurance. The ice is heavy and you have to work long hours to create what is a momentary wonder. They are truly living in the moment, and make their art for the beauty and joy of it."